From the Gulf of St. Lawrence

to the Golden Gate, America's

destiny followed trails blazed

by forgotten heroes—lonely figures

in homespun and buckskin.

This book tells the stories of

some of those daring men of the

BUCKSKIN BRIGADE

HOLIDAY HOUSE, NEW YORK

SEVENTH PRINTING

Copyright, 1947, by Jim Kjelgaard

This book is a tribute to daring men whose names are forgotten, but whose deeds and spirit illuminate every page of American history. As the westward march of civilization made its slow way over and through successive barriers of forest and prairie and mountain until it had spanned three thousand miles from ocean to ocean, it followed the moccasined paths of nameless men in buckskin. Always, beyond the towns, the settlements, the log-cabin clearings, were "the adventurers of the far side of the hill."

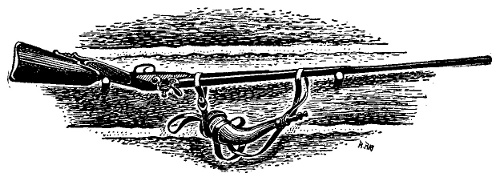

Woods runners, rivermen, long hunters, scouts, fur traders, and mountain men, these trail blazers were bound by no frontiers and limited by no horizons. Let the homesteader and land speculator and politician follow them; their world was illimitable and their only law the law of survival. By moccasin and snowshoe, by canoe and horse, protected only by their wits and their long rifles, they led the way into the unknown. They starved, froze, drowned, and were murdered by beast and Indian. But they lifted the veil of secrecy from the North American continent and showed other men the way to security, wealth, and fame.

The chief characters in these stories are real, although few will be familiar. Each one is representative of a period and a type—if such rugged individualists can be typed. Known facts have been used wherever possible, and the fiction which supplements and gives life to those facts has always been governed by a sense of probability. The stories have been arranged chronologically, and historical perspective maintained by brief factual introductions.

| 1506 | THE TREE | 1 |

| 1588 | CROATAN | 33 |

| 1615 | THE MEDICINE BAG | 63 |

| 1661 | SAVAGE TREK | 91 |

| 1753 | THE OPENING GATE | 125 |

| 1780 | WILDERNESS ROAD | 161 |

| 1791 | CAP GITCHIE'S ROOSTER | 183 |

| 1808 | THE FIFTH FRIEND | 213 |

| 1833 | FREIGHT FOR SANTA FE | 243 |

| 1844 | END OF THE TRAIL | 281 |

The importance of John Cabot's explorations in 1497 was not the discovery of a "New Found Land," but his report of seeing vast numbers of cod in the region now known as the Grand Banks. Fish were a staple article of food in the Catholic countries of Europe, and French, Portuguese, and Basque fishermen lost no time in tapping this new source of supply. Within ten years the sturdy little craft from the French channel ports and the Bay of Biscay were making regular runs across the dangerous North Atlantic, and bringing back more and more reports of the lands that lay about and beyond their fishing grounds. Hardy Breton and Norman seafarers established a proprietary interest in these distant shores that lasted for a hundred years. It is singularly fitting that the oldest surviving European name on the Atlantic coast of North America is Cape Breton Island.

Thomas Aubert relaxed on the coil of rope, contemptuously watching fussy little Captain LeJeune. Nobody but a Basque from St. Jean de Luz would stand at the prow of a ship, holding a glass to his eye and trying to peer through a fog that you couldn't cut with a scaling knife. But what could you expect from a Basque, anyway? God knew that the only true sailors, those really weaned on salt spray, were Bretons—preferably from St. Malo. No doubt Captain LeJeune and his five funny sailors were very good oyster shuckers, and certainly they were unexcelled as garlic eaters. But it took men from St. Malo to sail a ship.

Aubert cast his eye down the deck to where Baptiste LeGare and Hyperion Talon, two other St. Malo men crazy enough to sail under a Basque captain, were standing unconcernedly. They, too, had known for some days that the Jeanne was off her course. But, naturally, Captain LeJeune knew everything and certainly didn't intend to take the advice of any St. Malo men. They recognized none of this sea. Thirty-two days out of St. Malo, they should have been on the Grand Banks six days ago. But where were the hordes of waterfowl that hovered over the Banks? Where were....

Aubert braced himself instinctively, anticipating the shock a second before it came. Out of the sea loomed a great, shapeless mass, and the Jeanne[Pg 4] quivered like a woman in pain. There was a tortured scream, and the crack of rending timbers. Aubert saw Hyperion Talon go down, and shook his head angrily. If there was one floating object in all the North Atlantic, you could trust a Basque captain to find and hit it.

Then the floating iceberg passed on and the Jeanne righted herself. But there was a dangerous list to starboard, and with that innate knowledge of ships which generations of seafaring ancestors had instilled in him, Aubert knew that she was mortally wounded. He made his way toward the stern, and bent over the recumbent Talon.

"Are you badly injured?" he asked.

Hyperion shrugged. "I have a pain in the side. It will pass."

"Wait here," Aubert commanded. "I will return."

He joined Baptiste LeGare, who was scornfully watching the frantic efforts of Captain LeJeune and his five men. You could rely on Basques to panic every time. They were acting as though they had less than half a minute to launch their fool boat, when, as a matter of fact, they had a full half hour. Maybe more. The Jeanne was a stout little craft, and would take a lot of water in her hold before she finally settled.

The boat struck the water, and the five Basque sailors pushed into it. Captain LeJeune sputtered at them and ran back into the cabin. He emerged a[Pg 5] moment later with the ship's log under his arm. Aubert's brown eyes twinkled, the wind-etched wrinkles in his face deepened, and his black beard jerked as he suppressed a chuckle. LeJeune had launched a boat without water, without food, without anything except oars. But he had to save his precious log. Aubert laughed outright.

"What's so funny?" Baptiste LeGare demanded.

"The little captain," Aubert grinned. "He has taken his log with him. Can you not imagine it, Baptiste? One hour from now, if it has also occurred to him to take a goose quill and ink, he will be making some such entry as, 'June 5, 1506: The Jeanne, somewhere off the Grand Banks of the New Land, struck an uncharted reef and foundered. The three men from St. Malo were carried overboard by heavy seas.' Bah! Basque sailors!"

Lying prone on the deck, his head pillowed on his sea cloak, Hyperion Talon turned his head to look.

"Where are we, Thomas?" he inquired.

Aubert shrugged. "In the Atlantic Ocean, Hyperion. And that, in truth, is all I know. How is your side?"

"It has felt better; it could feel worse. Are the fools from St. Jean de Luz gone?"

"They are gone."

Aubert gravely regarded his fellow townsman and shipmate. There was blood on Hyperion's mouth.[Pg 6] Aubert liked neither the look of his eyes nor the pallor of his face. He raised his head and watched the little boat, whose sailors were frantically pulling away into the mist. Apparently they were going in no special direction. Well, they'd end up somewhere, if only at the bottom of the sea.

Aubert said, "Our turn, Baptiste."

LeGare followed him, and they broke out the little twelve-foot dinghy that was roped to the side of the cabin. Aubert regarded the dinghy fondly. It was a St. Malo boat; he'd made it himself. He knew what had gone into it and what it would stand. After Captain LeJeune and his men had capsized in their clumsy Biscayan lifeboat, the dinghy would still be floating. Grasping either end, he and LeGare carried it to the settling stern of the Jeanne, over which waves were beginning to break.

"Put in three casks of water and a keg of biscuit," Aubert instructed. "We'll need adzes, chisels, knives, mallets—you know the tools she'll hold. One musket, with plenty of powder and shot, should be enough. Also a coil of rope and a pulley."

LeGare began to load the dinghy while Aubert went below. The hold was gloomy and foul smelling from the countless tons of fish the Jeanne had carried during her many trips to the Newfoundland Banks. Aubert looked at the soggy heap of salt that was supposed to be thrown over the fish they took this trip,[Pg 7] and at the little stack of chests loaded with trade goods for the savages who were sometimes encountered when a fishing boat put into a New Land harbor for water and fresh meat.

Aubert shook his head disapprovingly. He hadn't liked it when they left St. Malo. He didn't like it now, this idea of a captain taking along trade goods to feather his own nest while he was catching cod for the ship's owners. To be sure, there was money to be made so doing. He had known the savages to trade as many as ten fine fox pelts for one tin plate and a few trinkets. But a fishing boat should do nothing except fish, and if anybody wanted to send a trading boat over here it should do nothing but trade. However, there really were not enough of the New Land savages, nor did they have sufficient furs, to justify anyone's sending a ship over just to trade for them. The captains got what there were. But to mix fishing and trading was a breach of propriety that somehow was sure to bring bad luck. Still....

On sudden impulse Aubert caught up a small chest of trade goods and carried it with him when he went on deck. He cast an expert eye the length of the Jeanne. She had settled perceptibly since he went below. Aubert stowed the little chest in the dinghy. LeGare stood by, the oars in his hands, staring into the mist-wreathed sea. Aubert inclined his head toward Hyperion Talon.[Pg 8]

The injured man groaned when they lifted him, and bright blood bubbled from his mouth. They laid him in the dinghy, with his head on a cloak and another over him. Aubert held a bottle of brandy to his lips. The half-conscious sailor took a feeble gulp, and smiled wanly. For a moment Aubert stood over the dinghy, checking its contents. But LeGare had done a good job, both in selecting and packing. Aubert returned, wrenched the compass from its stand by the tiller, and carried it to the dinghy. He and LeGare took their seats.

A few minutes later the Jeanne's stern went under and the little dinghy floated free. With a half-dozen lusty strokes of the oars Aubert sent it clear of the deck. He and LeGare turned around. Talon weakly raised his head. There was a swirl of water and for a moment the Jeanne stood upward, her bowsprit in the air as though beseeching aid.

The fog closed in.

It was very thick, a sinuously undulating cloud that sent clammy fingers into every nook and corner of the dinghy and touched the backs of the men with cold hands. Aubert raised the compass, gripped it between his knees, took a bearing, and swung the dinghy. Talon had fallen asleep, the cloak pulled up to his eyes and one hand peacefully upraised. LeGare,[Pg 9] a mist-shrouded figure on the stern seat, hunched his shoulders.

"What course?" he asked.

"West."

There was a thoughtful silence as LeGare digested this information. A lone gull squawked out in the fog and Aubert stopped rowing to listen. You couldn't tell much about gulls. They might be anywhere. Some followed the fishing boats clear from France. Some, apparently, lived in the middle of the sea. There was one chance in a million that this one presaged the nearness of another ship. Aubert shrugged. It would be impossible to find another ship in this fog, anyway.

LeGare spoke again. "It is a wise plan, Thomas, one that I would expect you to conceive. By going west we encounter a fishing boat on the Banks, eh?"

"We are not on the Banks."

"But we cannot return to St. Malo by going west."

"Consider, Baptiste. Could we reach St. Malo in a twelve-foot dinghy, even this one?"

The gull squawked again, faintly, then only the fog was left. The sea heaved a little, lapped at the prow of the dinghy. A wave splashed over it and Talon muttered sleepily as spray blew in his face. LeGare looked at the injured man as he replied.

"Of a certainty, Thomas, we cannot reach St. Malo. But what lies to the west?"[Pg 11]

"I do not know. I have heard men say that the shores of China lie in that direction."

"A long way, my friend, is it not?"

"Perhaps. But which is better, Baptiste? We know that we cannot return to St. Malo. We may reach whatever lies ahead, and if we do we shall find means to survive. Meanwhile, we are on the sea, and what man of St. Malo hopes to die in bed?"

"You are right," LeGare said philosophically. "We may trust the sea."

Talon sat up, and Aubert turned in his seat to look at him. The injured man's face was no longer gray, but red. His eyes were bloodshot, his smile forced. Aubert dropped the oars, broached a cask of water, poured some into a tin dish, and passed it back. Talon drank thirstily, fell back into the bottom of the dinghy, and coughed. Aubert crossed himself, and looked gravely at LeGare as he picked up the oars. He rowed strongly, evenly, taking long sweeps that produced a maximum of forward effort with a minimum of exhaustion.

After three hours LeGare said thoughtfully, "You remember Basil LeSeur, the old man who hung around the docks at St. Malo? He has been to the Grand Banks and the New Land many times, and he himself told me that he thought the New Land might be an island, perhaps many islands. He said he thought there might be other land not far from it.[Pg 12] Perhaps, after all, we shall come to the coast of China."

"Perhaps we shall."

He rowed on into the mist, pushing the little dinghy forward with powerful sweeps that curled the water at her prow and left a wake behind. Reason told him that theirs was a very serious predicament.

But something else within him stirred, something that, had it not been tempered by Talon's suffering, would have been only delight. Starting when he was thirteen, he had come six seasons to the Grand Banks and had helped catch great numbers of fish to take back to a Catholic Europe. Now, at nineteen, the Grand Banks and the bleak New Land had lost their charm, and the long trip from St. Malo had become dreary routine rather than high adventure. But Aubert had looked at the uninviting New Land, and yearned toward what lay beyond. Certainly the fabled Orient must be somewhere to the west. Now, at last, he was going toward it. Even though he had only a dinghy, and probably would never get there, at least he was trying to do so. If he could change his own fate now, he would not.

A wind stirred and the mist lifted for a little while to reveal a gray sea. LeGare took the oars, and night closed in. Aubert slept, with his head pillowed on his knees, and it was still night when LeGare awakened him to resume rowing. Talon muttered in delirium.[Pg 13] Little wavelets rose, and when morning came the fog had again closed in. Talon sat up, and gripped the side of the dinghy with the great strength that sometimes comes to dying men.

"Tell Catherine Minot," he gasped, "that she should not weep for me. There are other good men in St. Malo."

Talon collapsed limply, and his suddenly pain-free eyes seemed to be staring at some happy thing that only he saw. The sea was about to claim another St. Malo sailor. Aubert crossed himself, and in the stern seat LeGare followed suit. But LeGare's simple face reflected fear and doubt.

"How shall we administer the last rites?" he whispered.

"We cannot, Baptiste. We are no priests."

"Well then, how shall we bury him?"

"In the sea."

"But the sea monsters?"

"Fear not, Baptiste. The good God, who marks the sparrow's fall, will let Hyperion be claimed by neither the devil nor a sea monster."

"That is so," LeGare answered doubtfully. "We must have faith."

Aubert turned around, for a moment cradled Talon's limp body in his arms, and slid it over the side. He was no priest, but he murmured a prayer as the gray sea closed in about his comrade and took[Pg 14] him to its bosom. Aubert resumed rowing, averting his eyes from his companion's. This was the way things had to be; the living could neither help nor harm the dead. For a long way he rowed furiously, seeking in hard physical labor surcease from mental anguish. Then he changed seats with LeGare, and sat huddled in the stern while the stout little dinghy plied westward. Night came again.

Morning followed it, and another night and another morning until Aubert lost count. They were rowing mechanically now, robot men in an unreal boat on an endless ocean. For days they had not spoken. Exhaustion had laid its heavy hand on LeGare's face. When he rowed, his head drooped, and when he rested, he dozed fitfully. All day the mist followed them, and the nights brought no stars. LeGare held the last water cask up, and the few spoonfuls remaining within it gurgled. He offered it to Aubert, who shook his head and rowed on while he licked parched lips. LeGare looked longingly at the cask, corked it, and put it back of him, out of sight.

Aubert thought that it was about the middle of the night when something grasped the oars. He tried to wrench them away, and could not. All about were splashings and disturbances in the water. Aubert gave all his strength to the oars, and moved them slightly. His hoarse voice cried out, "Baptiste!"[Pg 15]

But LeGare was lying in the dinghy, snoring sonorously. Aubert groped for the musket, was unable to reach it. A strong, heavy odor pervaded the air, and the splashings in the water came nearer the dinghy. A loud bell seemed to be ringing in Aubert's ears, red fire danced before his eyes. They seemed to be moving, either in a westward current, or else whatever had gripped the oars was pulling them along. Again Aubert tried to reach the musket, and at last got it in his hands. But he could see nothing, and it would be senseless to waste a shot unless there was something at which to shoot. But when he tried to stand up he stumbled forward in the dinghy. Again and again he tried to rise, and see. But at last he lay still.

He awoke to a hot sun streaming out of a cloudless sky, and looked around in bewilderment. A great herd of dolphins was playing about the dinghy, splashing and diving as they went northward. Aubert blinked, and stared wonderingly at his hands. The dolphins—a good omen for fishermen—were what he had heard last night. There had been nothing on the oars. His hands and his strength had failed him, that was all. Aubert looked behind, and a hoarse shout broke from his parched lips.

"Baptiste!"

LeGare awoke grudgingly, rubbing his eyes with the backs of his hands. Both men stared, fascinated,[Pg 16] at a spit that jutted out from a great expanse of land.

In the very center of the spit, a mighty pine stood majestically in the morning sunshine.

A half hour later Aubert beached the dinghy on the stone-studded flank of the narrow spit and stepped into shallow water to pull the little boat farther up. LeGare joined him. The two staggered forward, unable instantly to adjust themselves to the feel of solid earth beneath their cramped legs. Lush green grass covered the point, and ripe strawberries gleamed redly through it. Aubert looked at them, and licked his lips. He glanced at LeGare, who was staring in fascination at the berries' rich redness. Aubert dropped to his knees, solemnly plucked a berry, crushed it between his fingers, and let the red juice stain his hands. He plucked another, almost reverently placed it in his mouth, and very slowly ate it. Then, with LeGare beside him, able to think of nothing else, he ate berries. An hour elapsed before they arose to look about them.

About a quarter of a mile long, the spit jutted from a dark green forest. On the other side was a sheltered bay. At its edge, a number of moose were feeding in the shallow water. Across the gulf, very far away, was the dim outline of more forested land.

"This is not the New Land!" LeGare breathed. "It[Pg 17] has no such great beasts as those. Sacré Dieu! It must be China!"

"Perhaps, although I have seen such beasts in Norway. But I never saw them enter salt water."

"Then we cannot be in Norway. But consider the size of those horns!"

Aubert picked up the musket and led the way down the point. The strawberries crushed under their feet. A flock of partridges that had been eating them walked indifferently out of the way. An otter climbed out on the spit, looked at them with beady eyes, and dived back into the water, startling a flock of ducks into flight. A cow moose raised its mulish head and swung to face them. Aubert marvelled. Wherever they had come to, it was a very rich land, indeed. And there was something about it.... He turned to look again at the enticing horizon across the gulf. If men had ever been here, he had not heard of it.

They reached the mainland, and circled the bay to[Pg 18] come upon a sparkling little river. A huge trout broke the surface and settled lazily back to lie fanning its fins. Aubert and LeGare threw themselves prone by the river to drink, and rose to smile at each other. A yearling moose, its neck out-stretched, snuffled toward them. Back in the forest a slim doe stamped its foot, uncertainly.

"This is an unviolated land!" Aubert said wonderingly. "No man has yet taken toll from it!"

He squatted beside the bay, looking over the water spread before him. What was the great gulf that met his vision? Did it lap the shores of another New Land, one upon which no man had yet placed foot? Was there a passage or strait that led through it to the fabled shores of China? He had to know, but how was he going to find out? If only the Jeanne were here, instead of at the bottom of the Atlantic where the blundering Captain LeJeune had sent her! If only he could explore this gulf, know what lay in it instead of tormenting himself with thoughts of what might be!

His glance roved back to the spit of land, and the great pine in its center. It was a huge tree, tall as any he had seen in Norway, and its massive trunk probably could not be encircled by the combined span of his and LeGare's arms. Aubert leaped erect.

"Baptiste, we shall make a ship!"

"You are mad!"[Pg 19]

"No! There is our ship! That pine! We have adzes, chisels, saws, augurs!"

"It will take years!"

"What of it? What is time to us now? See, beasts that will scarcely move aside to let us pass, fish and birds in vast abundance. Can even a lazy man starve here? Can he freeze, with unlimited quantities of wood to burn? We shall start our ship now, and when the season changes build a house!"

"But...!"

"We must gain knowledge of this land, much knowledge, and then...."

"But one cannot build a ship on an empty belly," grinned the practical LeGare. "Let us eat first, my friend."

They unloaded the dinghy. LeGare had forgotten nothing. There were most of the tools that a fishing boat carried, as well as fish-lines, hooks, flint and steel, and even tin plates. They dragged their dinghy up on the spit, upended it, propped the end with a cairn of rocks, and carefully placed their supplies beneath. Aubert attached a hook to a line, weighed it with a pebble, and experimentally whirled it about his head.

"We saw many fat fish in the river," he said. "They should be honored to provide a feast for men of St. Malo. Build a fire, Baptiste, and your greedy belly shall be filled."[Pg 20]

Aubert walked back to the forest, a little faster now and not stopping to look at anything else. Hunger, he reflected, was a demanding master. It was indeed an honor to set foot where no man had ever trod before, but LeGare was right. A fish still in a river took precedence over a tree on the shore. He overturned a rock, plucked a fat cricket from beneath it, and impaled it on the hook. Swinging the line about his head, he cast far out into the river, and almost at once was fast to a fighting trout. Aubert hauled it in, rebaited his hook and cast again. He caught another trout, and another, and marvelled. Even in virgin Norway it was impossible to catch big trout so fast. He carried the fish back on the point, watched LeGare split and clean them, and set them to broiling over the fire he had built. When they were cooked both men ate prodigiously, and Aubert sighed. Certainly whatever coast they had come to was a fine place to be. His curiosity returned.

"There are many duck's nests along the river," he said. "The eggs should be fine eating."

LeGare took the hint and departed. No sooner had he left than Aubert took an adze, stood beside the huge pine, and swung at it. The outer bark chipped away, revealing the orange-yellow inner bark. Sweat began to stream down his forehead as the sun shone hotly. He removed his shirt, laid it on the ground beside him, and continued to work on the tree.[Pg 21] Baptiste had been right. It was going to take a very long time just to fell the tree, much longer to fashion a ship. But certainly they were going nowhere without a ship.

LeGare returned, his doublet laden with duck's eggs. He pierced their ends and put them in the fire to bake while he went about arranging the camp. Aubert continued to work. By nightfall the huge pine that for hundreds of years had stood its lonely guard was well girdled. White chips littered the earth about it. But it was after nightfall when Aubert ceased his labors and crept under the dinghy to sleep.

Aubert was awake very early. Light mist blanketed the bay, lazy smoke rolled from the ash-banked fire. The moose had not yet come to the mouth of the river, but twenty curious deer stood on the spit, watching. A doe stamped her foot and advanced to within a few feet as she smelled at the chips from the pine. Aubert studied her. When cold weather brought assurance that meat would not spoil, he and LeGare must take a number of deer, and perhaps a few moose. Also, when the work of chopping down the pine and fashioning a ship from its trunk became too wearisome, they could catch and dry a number of fish. In the act of prodding the ashes to stir up the fire, Aubert stopped suddenly.[Pg 22]

The lightening of the mist under the rising sun revealed a birch-bark canoe with six paddlers coming down the bay. Aubert crawled under the dinghy and shook LeGare's shoulder. LeGare came awake, and sat up slowly.

"Savages approach," Aubert whispered. "They look not unlike those who visited our ships when we anchored off the New Land. Take up an adze, and stand ready to repel them if they are hostile."

Aubert picked up the musket, put a horn of powder and a pouch of shot beside him, and sat in the grass awaiting the canoe. The paddlers were all men, with well-developed arms and shoulders, and Aubert noted approvingly that they handled their frail craft with ease and grace. Apparently these savages were seamen, not afraid of the water. Their heads were shaven save for a long strip, oddly like a horse's tail, down the center. Their cheeks were painted with some sort of roan pigment.

LeGare, standing beside him with the adze, whispered, "They are not wholly like the savages of the New Land."

"No. Their hair is of a different arrangement. Let us see what they want."

As the canoe hove to in shallow water, the Indians stepped out and waded ashore. A breechcloth flapped about the waist of each, and each had a stone axe and knife thrust into a buckskin belt. Five of them wore[Pg 23] moccasins fashioned of deerskin and decorated with stained porcupine quills, the sixth was barefooted. A hawk's wing was thrust into the pierced ear of one, while the rest wore the skins of crows suspended from their belts. He of the hawk's wing, apparently the chief, held up his hand with the palm out.

"The peace sign," Aubert murmured. "They do not have hostile intentions."

Aubert stood up, showed his palm and walked three paces forward. The Indian grinned, childishly pleased, and with his five solemn followers trooping behind him stalked up the bank. They squatted down by the dinghy, and broke into an unintelligible gibberish as they poked inquiring fingers into its side. The chief reached for the musket, and when Aubert snatched it aside, drew sullenly back.

"Break open the chest," Aubert instructed LeGare. "It is well not to anger them. We cannot fight them off if they come in sufficient numbers, and angry. Presents may pacify them."

LeGare opened the chest of trade goods, revealing the shiny red ribbon, beads, cheap little knives, needles, and other knicknacks within. Gravely Aubert picked up a handful of red beads, gave two to each of the men, and four to the chief. Smiles lighted their faces and chuckles rolled from their throats. A tall Indian with two ugly scars running the length of his ribs laid his beads on the grass and watched in childish[Pg 24] delight as the sun's ray glanced from them. The chief held his in the palm of his hand, his awed eyes staring from them back to the chest. He gestured toward it.

"Close the chest," Aubert ordered. "We may have much need of what is there."

LeGare slammed the lid down, and the six Indians sat looking from the treasures in their hands to the incalculably greater amount still in the chest. No one spoke. A flight of ducks glided out of the sky, and came to rest on the placid bay. Aubert looked at the sullen savages, now beginning to mutter among themselves. What if they decided to take the chest? Out of the corner of his eye, Aubert saw the ducks, scarcely a stone's throw away. Wheeling suddenly, he levelled the musket and shot over the heads of the Indians. Out on the bay eight ducks either lay quietly or beat the water with dying wings, while the rest of the flock paddled about in confusion. The chief fell backward, and rose to clench his hands to his breast while he looked at the gun with frightened eyes. The rest ran to the water and splashed to their canoe. The chief ran after them, and paddles flashed furiously as the canoe sped up the bay. Aubert gazed thoughtfully after them.

"They have never seen white men nor heard guns," he said. "I did not like to waste the shot, but it is well to have them know that we can protect ourselves."[Pg 25]

"They are like children!" LeGare exclaimed. "They are more simple than children! Excited over red beads!"

"Well, they are gone. And I am going to fell this tree."

He picked up the adze and resumed his place beside the mighty pine, patiently hacking out chips, enlarging his cut as it was required to let the adze bite deeper. LeGare removed his clothing, and swam out to retrieve the dead ducks. He carried them up on the spit, and set about skinning them while Aubert continued to hack at the pine. The mysterious horizon across the bay beckoned, and the rippling waters in the great gulf called in a thousand different ways. Aubert swung the adze furiously. It was a hard thing, now that he had at last found some place he really wanted to go, to wait years to get there. But, no matter how many years it took, get there he would. The chopped wedge in the pine's trunk deepened, and chips piled thickly about his feet as he worked on. LeGare rolled the ducks in wet clay, and buried them beneath the fire. Then he went to the river and returned with the water cask filled. Aubert drank deeply, and went on felling the pine.

The sun had passed its zenith and was sinking toward the west when LeGare swung suddenly to look out on the bay. A startled exclamation broke from his lips. "They come again!"[Pg 26]

Aubert dropped his adze to look. Eight canoes, manned by from four to six men each, were coming down the bay. Wet paddles flashed in the sun. The paddlers strained forward, as though each were striving to outdo the rest and get there first. An excited, happy yell echoed over the water. LeGare turned questioning eyes on Aubert.

"They are very many this time. What shall we do?"

Aubert studied the advancing canoes, listening to the shouting of the men in them. Men bent on war did not come that way, or openly, but in the dead of night and silently. Beyond a doubt their first visitors had carried word of the strange interlopers back to whatever village they had come from.

"Give me the musket," Aubert said. "We cannot do other than let them come. But I do not believe that they come for war."

Out on the bay one canoe gained a long lead on the rest, and its paddlers hurled taunts and jibes over their shoulders as they sent their flying craft toward the spit of land. But the rest were deliberately holding back, Aubert saw. Not believing all they had been told, they were waiting to see what fortune or misfortune befell those in the leading craft before they themselves came in. The first canoe hove to. The chief with the hawk's wing in his ear stepped into shallow water and stood with his arms folded across his breast while he stared fixedly at Aubert. The paddlers[Pg 27] hovered nervously in the canoe, their upraised paddles ready to dip into the water.

"Why do they wait?" the puzzled LeGare inquired.

"They fear the musket," Aubert guessed.

He laid it on the grass before him, and a friendly smile split the chief's face. He waded back to the canoe, bent over it and lifted out a bundle of furs strung on a buckskin thong. Aubert gasped. They were glossy, shining sables, so many of them that the dangling string reached from the chief's shoulders to the earth. The chief climbed up the bank, a wild, stark figure against the bay. He looked suddenly down at the gun, and stopped in his tracks. Aubert nodded, understanding. The musket's power had been demonstrated, and to this ignorant forest prince of whatever land they were in, it was mighty power indeed. Aubert put the gun back under the dinghy, and the chief threw his string of sables on the ground. Aubert looked at them, marvelling. Furs such as these were not known in Europe. Even the fishermen from the New Land brought back nothing like them. The Indians pointed at the chest of trade goods, nodded vigorously, and again spoke in his own dialect.

"He wants to trade!" LeGare blurted.

Aubert shook his head dubiously. "Not for anything in our chest, Baptiste. Even a savage would not do that. Furs so magnificent for trinkets so cheap? He wants another present."[Pg 28]

Aubert opened the chest, took out a spool of red ribbon, cut from it a foot-long strip, and gravely gave it to the Indian. The chief snatched at it, muttered in delight, tied it around his left bicep, and stretched his arm to admire the shining cloth. He nudged the furs with his foot, picked up the thong that bound them and placed it in Aubert's hand. Aubert stared, dumbfounded, at LeGare.

"He did want to trade!"

The seven other canoes had arrived during this parley. Now the Indians scrambled out of them, splashing through the water and climbing up the bank as though each had to be first. Every one bore a string of furs: sable, ermine, otter, mink, beaver, lynx, fox. Gravely Aubert snipped off a twelve-inch length of ribbon for each offering, and the spool was scarcely half emptied when all the furs were piled about him. A huge Indian with a scarred face laughed, evidently displaying his contempt of the fools who would trade priceless ribbon for worthless furs that were to be had in endless amounts. Two Indians, with ribbons exactly identical, gravely effected a trade. Finally all sat down in a pleased semi-circle, admiring the bits of ribbon on their own arms and those on the arms of their companions. LeGare stared with unbelieving eyes.

"Thomas, we're rich!"

"True," Aubert agreed soberly. "A king's ransom."[Pg 29]

"But what are we going to do with them here?"

Aubert shrugged. "Sleep on them, Baptiste. A ship would be worth a thousand such piles of peltry to us now. I'm still going to fell the tree."

He took the musket from beneath the dinghy and laid it on the grass. The chief pointed to it, and guttural speech rolled from his throat as he spoke excitedly to his assembled comrades. A few of the Indians rose to go farther back on the spit, but most drew their feet a little farther beneath them and remained. Aubert watched closely, and finally turned away satisfied. The Indians were afraid of the gun. Aubert took up his adze and resumed chopping at the pine.

In the background the assembled Indians murmured pleasantly, and exchanged comments as they kept their eyes on this fascinating spectacle of a white man chopping down a tree with a strange instrument of metal. Aubert worked furiously, sinking his adze into the cut and drawing it out for another blow. The chief rose, made a wide circle around the gun, and watched from the other side. Half his warriors followed. A great cloud of waterfowl squawked overhead, and settled down to ride the little waves that a slight wind was kicking up on the bay. The sun, a blazing red ball, hung sleepily over its couch in the west. And it was just at that moment that the tree fell.[Pg 30]

A shudder ran the length of its mighty frame, and there was a sudden rending of fibers. The top of the pine swayed toward the water, and the Indians on that side scrambled to get out of the way. A mighty splash of water erupted from the bay as the upper half of the giant fell into it.

For a few minutes more the Indians stood about, greatly admiring this white man who could bring down so mighty a tree for no apparent reason. One by one they took to their canoes and faded into the twilight that hovered over the bay. When the last one had gone, LeGare dug into the pit he had made beneath the fire and brought out the roasted ducks. These they ate with wild strawberries, then for a long while lay watching the dark and silent gulf. The Indians knew some of it, but certainly a frail birch-bark canoe had never sailed clear around any water so vast. Only a ship could do that.

It was very late when Aubert finally fell asleep.

He was awakened the next morning by a shout, and lay still, doubting his ears. But the shout was repeated, and this time it came very clearly to him.

"Ahoy the shore!"

Aubert scrambled from beneath the dinghy and looked out on the bay, now doubting his eyes. There was a ship out there, a channel fisherman, riding at[Pg 31] anchor with furled sails! Aubert rubbed his eyes and looked again. There was no mistake. It was the Pensee out of Honfleur, commanded by Jean Denys. Aubert threw back his head and a great, bull-like roar burst from his lungs.

"Jean!"

"Thomas!"

Aubert watched a boat lowered from the Pensee, saw the bearded figure of Jean Denys in the prow. LeGare crawled from beneath the dinghy, clapped happy hands, and laughed. The Pensee's boat bumped the spit of land. Jean Denys stepped ashore, grinning.

"You Bretons get lost in strange places, eh? And, of course, Normans have to find them. What are you doing here, my friend?"

Aubert grinned back. "Showing the way to the men of Normandy. Welcome to Cape Breton!"

Denys laughed. "A good name, I admit. But where is your ship?"

"Foundered. It was a Basque ship, so no matter. Our ship is there," and he pointed to the great trunk of the pine. "True, it is not quite finished."

Jean Denys whistled in admiration. "It has already earned your passage to St. Malo," he said soberly. "We were about to turn back last night. But I was looking through the glass and saw a tree fall. Such a tree does not fall by itself. Voilà. I am here."[Pg 32]

"But this is not the New Found Land. What were you doing here?"

"Exploring. Ship's owners gave me permission to spend four weeks doing it and see if I could find new fishing grounds."

Aubert's eyes glowed, but he tried to make his voice casual. "What did you find?"

"It's a vast gulf, Thomas." He swung suddenly to look Aubert squarely in the eyes. "That horizon you see over there is an island. Beyond it is a great expanse of water to a forested shore. And, Thomas, at the far western end of the gulf there is a passage through the land!"

"No!"

"Yes! And who knows where that leads to?"

Their eyes met, understandingly, and together they swung to face the enticing, unknown west.

Thomas Aubert did come back. Two years later he sailed part way up the St. Lawrence, and thus pointed the way for his fellow Breton, Jacques Cartier, a generation later. New France had begun.

But during the Sixteenth Century England was too busy watching the rival power of Spain to worry much about the activities of a few French fishermen and fur traders who had capitalized on the English-sponsored expeditions of the Cabots. Not until the end of the century did Sir Walter Raleigh undertake his two ill-fated experiments in colonization, and then he chose a region far south of the St. Lawrence, on the more temperate shores of the Carolinas.

The lost colony of Roanoke was, and remains, the most famous mystery in American history. It was also a complete failure. But it showed the shape of things to come, for its purpose was neither trade nor conversion, like the French settlements to the north, but colonization. It was to be a new home for Englishmen, and it was no accident that an English child was born on Roanoke Island thirty years before the first French woman sailed up the St. Lawrence.

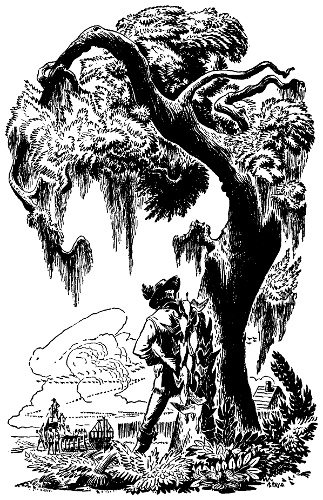

Flight after flight of little green-winged teal dipped out of the sky to settle on the slough. Their flapping wings churned the water into a froth, and those already on the slough scarcely moved aside as others sought to enter. It seemed, Tom Weston thought, that there was no water at all, but only successive layers of teal, with the final row of bobbing heads and restlessly moving wings on top. But newcomers always found a place.

The teal were harbingers of cold weather. Last year their vanguard had arrived on the fifteenth of October, two months after Governor White had sailed to England—supposedly to return within nine months with more people and more things for them to work with. Not that there was any real need of that. If a hundred men and a dozen women couldn't support themselves on an island like this, then only the Lord could help them.

When the colonists had first arrived, they had expected both to be welcomed and to find plentiful stores waiting. But the savages who inhabited this Roanoke Island—or at least came to it whenever they aroused enough ambition to paddle—had destroyed or carried off the stores and killed the fifteen men left to guard them. That had been an unpleasant shock to the men and women who had landed on this island fifteen months ago, in the year of Our Lord, 1587. And that shock was their principal trouble.[Pg 36]

Well, maybe it wasn't. Most of them had listened to glowing tales of great wealth and easy living when they had embarked for this new colony of Virginia. Everything, they had been told, would be waiting for them and they had only to lift a hand now and again in order to ensure themselves a richer and finer life than they had ever known before. Because nothing had been waiting for them, and there had been no one to tell them exactly what to do, they didn't even want to lift that hand.

A great horde of teal swooped down and somehow crowded in among those on the slough. There was a mighty quacking gabbling, and Tom rose suddenly from the log behind which he had been crouching. As he did so his right hand was whirling a crude, homemade bolo—four buckskin thongs attached to holes in pierced shells. There was a deafening roar of wings, and an immense splashing of the water. The bolo sailed into a veritable horde of ducks, and when it dropped to the slough five of the little teal were entangled in its serpentine coils. Tom waded out to retrieve his kill, dropped them behind the log on top of the twenty-three he had already captured, and again concealed himself until the settling teal came in closer.

He lay indolently, letting the sun caress his back and warm his legs. Of course that warm sun wouldn't last very long; frost would follow the teal within six[Pg 37] weeks. When the great, black-necked, white-throated geese appeared you could be certain that frost would come almost within a day. It didn't make much difference. There were no crops to kill because those who should have been planting had instead passed their time on the shore watching for the ship from England. When that came there would be no need of crops because there would be food in plenty.

What the colonists should have known, but did not, was that the ship wasn't coming. It was impossible to look across the Atlantic Ocean and see that Elizabeth's England was again at war with Spain. John White had said that he would be back and the colonists had been watching for him since spring. Now it was October, and the earliest a ship could come was next April or May. No captain cared to risk his sailing vessel in the Atlantic while it was lashed by storms.

If only the colonists would work, and look to that which was all about them for their own salvation! But they would not, and now their confusion and hopelessness would be multiplied tenfold. Ananias Dare, son-in-law of John White, husband of Eleanor, and acting governor of the colony while John White was away, had died yesterday. He had done as well as he could, but Ananias had been ailing for the past six months and a sick man could not carry out his own orders. Now that he was gone, and no authority[Pg 38] reigned, there was bound to be bickering. All most of the colonists could think of was getting back to England, and the fool ideas they had for getting there....

Tom rose to throw his bolo again, and added three more ducks to his catch. He could stay here all day, and all tomorrow, and the colony could still eat all the ducks he was able to catch. But somebody had to hunt, and they depended on him because he was better equipped than any other to get along in this new land. He had been self-supporting since he was eight, when his father had been cast into debtor's prison. Some of the methods he had employed in order to eat had proved useful, if not lawful. He had poached many a rabbit and grouse from manor estates and taken many a trout from the gentry's streams. He'd been tinker, pedlar, and vagabond, by turn. But fortunately he had become a cobbler's apprentice in London when John White stopped in to be fitted for a new pair of boots. Tom had listened, wide-eyed and open-mouthed, while White spoke of the second Virginia colony that Sir Walter Raleigh was organizing. Offered an opportunity to join, Tom had signed on two minutes later.

And, somehow, the land was all John White had said it was and very much more. Where, in England, could you stop at a slough and kill as many ducks as you wished? Where in England, outside your own[Pg 39] guild and social circle, could you consider yourself equal to any other man? Where could you walk anywhere at all, and be warned away by no keeper or bailiff? This Virginia had something England never would have. An unclothed man here, with no possessions other than those to be found at hand, was better off than—well, at least better than a cobbler's apprentice in London. Tom grinned wryly. He had been on the verge of thinking himself better off than an English lord, but he had no basis of comparison for that. Anyhow, under no conditions, was he going back. He must have been born to live a life like this. Maybe he was half savage.

But the savages got along all right. Only the wealthiest Englishmen ate as sumptuously as they did, and no Englishman was more free. The savages had the right idea. They worked when they felt like it, and loafed when they didn't. And nobody was more stealthy in a forest or more quiet in a thicket. They killed their deer, caught their fish, and even tilled their fields after a fashion. But certainly no savage would work in a London cobbler's shop from the first light of day until the last of night. That sort of life was fit only for those who liked it; probably almost any man on Roanoke would choose it in preference to what he had. But not Tom Weston.

He threw his bolo again, and retrieved the ducks entangled in it. Snatches of a hymn drifted to his[Pg 40] ears. The colonists should be finished with the burial by this time, and Ananias Dare resting in his forest grave.

He, the hunter, would probably be branded a heretic and a hopeless savage for not attending the funeral. But he was a heretic anyway for counselling that the colonists get busy and help themselves. And it was far more important to help those living than to attend the funeral of even a man like Ananias Dare. Tom knelt, and slipped the heads of the teal through loops on a buckskin thong. Two of the fattest he separated from the pile, and tucked inside his leather jerkin.

He started toward the settlement.

He broke out of the forest into a small natural clearing that swept to the sea. The huge, unwieldy skeleton of a quarter-finished sloop, made of adze-hewn timbers, was as prominent as a beacon fire on the east side of the island. Tom regarded it caustically. Simon Fernando, the pilot who had brought them over, was supervising the building of that sloop. Most of the men in the colony, who looked upon it as a means of going somewhere else—preferably back to England, but anywhere so long as they didn't have to remain here—worked on it from time to time. Tom sniffed audibly. Simon Fernando was a Spaniard and[Pg 41] a Papist, and the fact that Englishmen would listen to his plans at all was an indication of the low estate to which the colony had fallen.

Smoke from a lackadaisical fire drifted up through a wooden rack and curled lazily around three huge fish that somebody had caught. Beside them was a great pile of wild grapes, drying in the sun. Still desperately hoping that a ship from England would come, at least some of the colonists were awakening to the probability that it would not, and were starting out to gather a reserve of food.

They should have started in the spring. But better late than never. And nobody was going to starve anyway. Fish were easy to catch, there would be geese and some species of ducks all winter, and they still had three guns with which to bring down deer and bear. There were only half a dozen charges for each gun, but they could fashion bows and arrows when that was gone. The Indians killed big game with such tackle, and anything an Indian could do a white man could do better.

Tom dropped his string of ducks in the center of the square formed by the bark-thatched huts. A fresh-faced young woman wearing clothes that she had patiently fashioned from deer skins looked up from her cooking fire and smiled at him.

"Fresh barley bread and greens for a brace of those fowl, young huntsman," she called. "Is it a trade?"[Pg 43]

"It is that, Molly." Tom's white teeth flashed in a smile. "Here's two of the best for you and your John."

Clutching the two teal, Molly Gibbes disappeared into her hut. Other colonists gathered around. Old Granny Desmond, who at seventy-one still hadn't been too old to try something new, hobbled over and held up a pewter mug in her stained hands.

"Tom Weston, you've been gone since afore dawn!" she scolded. "Huntin' for idle folk too lazy to work! Here's summat to drink. The juice o' wild grapes won't touch a pint of English ale, but 'twill serve, if a body's thirsty. I've been pressin' it out all day."

"Thank'ee, Granny. And here's a duck for you. A fat one, too."

"Give it to those in need of it," Granny Desmond sniffed disdainfully.

"I'll give them where I please, you toothless old dame," Tom answered with a grin. "Don't worry, Granny; it will eat as tender as any sucking pig."

Molly Gibbes had come out of her hut and was staring at the sea. She took a tentative step toward the sloop, then walked up to touch Tom's elbow.

"There's trouble afoot, Tom, and I fear my John's temper. Look yonder."

Tom swung on his heel to stare at the little knot of men clustered about the sloop. John Gibbes, a square-jawed farmer who was one of Tom's few friends in the colony, was backed against the skeleton of the[Pg 44] ship. Simon Fernando, his head belligerently lowered and his expressive Latin hands gesturing, stood directly in front of him.

Dropping the ducks, Tom strode hurriedly down to the sloop. At a softly spoken word from one of the men behind him, Fernando turned away from John Gibbes. The slow-thinking, slow-talking farmer's face was red with anger, and his thick forefinger trembled as he pointed it at the Spaniard.

"I am a freeman here, and till my land at no man's order. No Spanish sailor will provision his ship with my grain, governor or no!

"And why not?" Simon Fernando purred. "Was I not chosen your new leader this very day? Will not my ship provide passage for all who have—how you say—cooperated?"

"No," Tom interrupted. "Firstly, if by chance this ship is finished, I doubt it will float. Secondly, it would hold but a score of souls. You delude the rest with false promises. You know full well our labor were better spent in making needful preparations against the winter."

Practical and true as they were, his words only angered the little group behind Simon Fernando. All of them wanted to go back to England, and they'd have been loyal to anything that promised even a faint hope of getting there. They believed in Fernando because they wished to. Even though only a[Pg 45] dozen people might go in his sloop, those nearest Simon would be among them. But here were two who would not.

Side by side, they walked back to the village, the ex-poacher who had found a free hunter's paradise, and the former leaseholder whose only landlord now was nature. John Gibbes was a stolid, unimaginative farmer, whose only loves had been his wife and the soil that his ancestors had tilled for countless generations. But he had found a new soil with neither rents nor restrictions, poor and unproductive though it was, and the harvest he had coaxed from it with patient skill he regarded as his rightful possession.

"So you would cling to your rocky fields, John?" Tom asked. "I could make you a hunter, if you would but try."

"Farming is in my blood," the older man replied. "'Tis all I know. Poor as this soil is, I would not change my lot."

Tom stopped suddenly. "This little island will soon become too small for Fernando's unruly crew and us. I have a plan. Meet me tonight at the little bay on the west shore. It's the bay with the three big sycamores in a line. Tell Molly I have asked you to hunt with me tomorrow."

Before the mystified Gibbes could answer, Tom turned on his heel and left him.

He walked to the last building, knocked softly, and[Pg 46] when a feminine voice answered, he rolled the skin door aside and entered. Light streamed through the unglassed windows to reveal in soft outline the neat interior. There were joint-stools and a carved chest from England, and English pots and kettles hung from hooks set in the stone fireplace. Fresh rushes had been strewn on the smooth earthen floor. There were traces of tears in the eyes of the young woman who knelt before the hearth. She rose to her feet.

"Oh, it's you, Mr. Weston."

"Yes, Mrs. Dare. I—I just stopped by."

"You are always welcome."

"I'm sorry about Ananias," Tom mumbled. "It was not right that he had to be taken."

"It was God's will," Eleanor Dare said softly. "How are the rest accepting it?"

Tom hesitated, then said bluntly, "They have chosen Simon Fernando in your husband's place."

Eleanor Dare nodded. "'Tis no surprise. Is there anything I can do for you, Mr. Weston?"

"Could I—er—see the baby?"

"Mr. Weston! You, the woods-runner, to take an interest in my babe! How long has this affair of the heart been in progress?"

"Since she was born."

"Virginia should be flattered!" Eleanor Dare laughed. "How many English girls, think you, have an admirer when they're scarce a twelvemonth old?"[Pg 47]

She went to the rear of the room, bent over a crude, homemade trundle bed, and lifted a golden-haired chubby-cheeked child from its feather mattress. Tom shrank away.

"What! Afraid to touch her?" Eleanor Dare smiled. She held out the baby toward him.

"Uh-oh, no," Tom said lamely. "I just wanted to look at her. And to give her—you, that is—these birds." He pulled the two teal from his jerkin and laid them on the hearth. "And if there's aught I can do, if you need help...."

"I won't forget," Eleanor Dare said soberly. "And thank you, Mr. Weston."

A round, yellow-orange moon rose to shine through the tall trees. The quavering whicker of a raccoon floated softly as the call of a ghost through the darkness. From somewhere out in the forest came a shrill scream. Tom walked on, unheeding and unafraid. The night woods were no more dangerous than those of the day, and when a grouse clucked sleepily in a tree he paused with one hand on the hilt of his knife. Slowly he walked two steps backward, his head bent. But he had to dodge and twist about, stepping from place to place, before he saw the grouse that had clucked and seven others silhouetted against the moon on the limb of a gum tree.[Pg 48] Cautiously he withdrew the knife from its belt sheath, and poised, grasping its tip with thumb and forefinger.

But he slid the knife back into its sheath. He had no other, and there was too much danger of loss involved in throwing it at night. Very slowly, making no noise, he withdrew the bolo. He threw that, and when it dropped to earth there was a sodden thud and a frantic beating of wings as a grouse dropped with it.

Tom picked up his game. Grouse were fine eating, much better than teal, and for a moment he thought of Eleanor Dare and her baby. But it was too late to return to the settlement now. He hadn't spent a night there in six months, anyway, because he liked the forest better. It was good to be away from people who seemed always at cross purposes and never satisfied.

Suddenly he stepped out of the trees onto a beach. The shining moon danced on the water, painting it with rich gold that little waves were trying to wash away. A raft of ducks—not teal but bigger, ocean-faring ducks—cast a shadow as they drifted across a patch of moonlight.

Tom walked to the base of a huge tree whose low-sweeping branches almost touched the water, and stooped to lift long streamers of moss from a canoe. Moss was a much better covering than almost[Pg 49] anything else because it stayed green. Withered foliage was a certain give-away to anyone who knew what should and should not be. Carefully he laid the moss at the side of his canoe, noting each piece so that it could be replaced, and examined the little craft that had taken so many painful days of labor.

Sixteen feet long, the canoe was fashioned from a single tree trunk, the ends of which had been shaped with adze and knife. The inside of the log had been burned out, and then scraped clean with the adze, to form a heavy but serviceable craft. An outrigger, a piece of buoyant dead log supported on green sticks, prevented the canoe's tipping even in rough water. A paddle lay under it.

Satisfied, Tom re-covered the canoe, then gathered a pile of tinder and struck a spark into it with his flint and steel. The tinder glowed, sparkled, and climbed into leaping flame. Tom added more wood. When the fire was blazing he dressed his grouse, rolled the unplucked bird in wet mud, plastered more mud about it with his fingers, and buried it in the fire to cook. When it was done the feathers would come away with the mud pack.

For half an hour he fed the fire, then suddenly stiffened in the act of adding more wood. Somebody was coming. Silently he stepped away from the fire and slunk behind the bole of a tree. His fingers curled about the hilt of his knife.[Pg 50]

But it was John Gibbes who, a moment later, broke out of the trees and stood peering about in the light of the fire. His russet doublet, leather breeches, and coarse kersey stockings looked oddly out of place in such wild surroundings. Tom grinned in the darkness.

"It's a poor hunter you'd make, John, with those great boots of yours. You sound like a west-country ox."

The farmer started, then smiled his slow smile. "That's as may be. But I've brought a loaf of my goodwife's bread, and a bit of souse. You'd hunt a long time in your plagued woods to find the like."

"Molly's bread is more than welcome, but here's something better than pickled fish."

Tom raked the grouse from the fire, cracked the mud packing from it, and broke the steaming bird in half. He laid both halves on the projecting root of a tree, and when they had cooled gave one to John Gibbes. They ate in silence, and after they had finished Tom sat staring over the moon-dappled sea at the dark, mysterious mainland. There was a great swamp just across the water over which he gazed. But what was beyond the swamp? Well, he was ready to find out at last.

"John," he asked suddenly. "What does England have that you miss here?"

"Well," John Gibbes said ponderously, "well,[Pg 51] kindred souls, you might say, for one. A mug of ale at the ordinary, now, and friends to drink it with! There's farmers enough on this island, but the land is poor, and that Spaniard fellow has made 'em shiftless. There's not a real husbandman left in the lot."

"But suppose there were a thousand farmers here?"

"They could never live on this godforsaken land," the practical Gibbes replied.

"But there's more land beyond."

"Aye, a wilderness."

"It may be," Tom admitted. "And if it were, I would not care. But you are a tiller of the soil, and want your neighbor to be, likewise. Suppose your neighbors had red skins?"

"What do you mean?"

"I mean that these savages on the mainland cannot live wholly by hunting. I know not where they get their crops. But they must have some."

"Do you mean there may be farmers yonder?" John[Pg 52] Gibbes asked, and for the first time there was a note of enthusiasm in his voice.

"I warrant there are. At least, I have fashioned a canoe, and mean to find out. Will you go with me?"

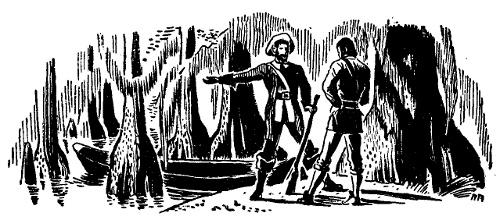

The sun broke over the trees, poured itself down on the water, and broke into a thousand little shimmering jewels as a breeze danced across the river in front of them. With John Gibbes, an apprehensive but stalwart passenger, Tom had paddled his dugout canoe over the water separating Roanoke from the swamp land and turned north along the swamp's borders. It had still been dark when he entered the mouth of what he had known was either a lagoon or river. Now, when he scooped up water in his hand and tasted it, he knew they had come into a river.

He drove the crude craft toward the bank, where they could be ready to disembark and run into the shelter of the trees if anything happened which made such a course necessary. But it was a peaceful river, a wild and primitive place which, judging by outward appearances, had not been disturbed since the beginning of time. Trees crowded to its very edge, and trailing vines interlaced them to dangle their ends in the water. A pair of cranes, snow-white save for a smooth red crest, lumbered awkwardly out of the water and flapped slowly away.[Pg 53]

"Tom, look you there! What is that ugly thing?"

There was a note of amazement and incredulity in John Gibbes' voice, but no fear. Tom looked at the fourteen-foot, greenish-black creature that floated on top of the river. It submerged until only its little balls of eyes showed above the water. Involuntarily Tom reached for his knife, then let the puny weapon slide back into the sheath. John White, who had sailed along the borders of this land—Croatan, he had called it—had said that many strange things inhabited it. He had spoken truly!

Tom drove the dugout forward, cleaving the water with long, clean strokes of his paddle, and watching the dark, tree-fringed shore on either side. Ahead of them a little sand spit jutted into the river, and on it a herd of deer stood gazing curiously at the dugout. Their heads outthrust and their long ears alert, they stamped their feet as though in cadence to the rippling wake that curled from the stern of the canoe. A million birds seemed to call among the trees, and an unconcerned black bear watched the dugout slide past. This was a forgotten land of unimaginable plenty, a place where a man might find anything, and live forever without need, fear, or restraint.

"Tom, do you note the blackness of the soil, and how lush the vegetation? 'Tis the richness of the river silt, I reckon."

With a jerk Tom's thoughts were dragged out of[Pg 54] the clouds and back to the passenger in his dugout. He saw unfettered opportunity, John Gibbes saw fertile land. But that was the way it should be. This land had everything to offer. It was a challenge to the man who had never known contentment elsewhere, and a promise to him who wished only to till its soil. Neither Roanoke nor England itself had that.

The river narrowed, and Tom edged the canoe away from the bank. Nothing had appeared to dispute their way. It was almost inconceivable that, in so wealthy a land, there should be no one to enjoy it. He drove the canoe around a bend in the river, and almost before he was aware of it the trees to his left gave way to a big clearing.

In the center of the clearing was a small village of bark-thatched huts, surrounded by fields of standing corn. Pumpkins yellowed on the vine among the cornstalks. Nearer the huts were other fields that bore, Tom guessed, the new world crop which Ananias Dare had described as potatoes.

Not until then did he notice the half-dozen men who had been sitting indolently on the bank of the river. Almost imperceptibly, dipping his paddle as lightly as possible, Tom edged the canoe toward the center of the river. Attired only in breechcloths, moccasins, and necklaces or armbands, the savages had risen to stare curiously. One turned to gesture toward the village. More men and boys, even women with[Pg 55] babies tied to their backs, streamed down to the river's edge.

"Let us land," said John Gibbes in sudden excitement. "They do not appear unfriendly."

Tom swung the canoe around cautiously. You never could tell about new people. There was always the possibility of a trick, and he had no wish to step into a trap. But none of the Indians were armed, and who gained anything without venturing? Tom hesitated another second, and then drove the canoe toward shore with long, deep strokes of his paddle.

The dugout grated softly on the river bank. John Gibbes stepped out, and without hesitation started toward a group of squaws who had stopped work in the cornfield to stare at the strange visitors. Tom followed, and the remainder of the village's population trooped amicably by his side.

Gibbes turned to him, held out a handful of the rich, black earth, and crumbled it between his fingers.

"There's naught like this in all England," he said reverently.

Tom turned to look at the forests that hemmed in the little clearing, and his own excitement leaped higher. This, assuredly, was the place for a man. He could go as far as his own strength and courage would take him, the only obstacle his own indolence. This was an unbelievable land. Probably not even Governor White had known of its existence. If the[Pg 56] Roanoke colonists had only been brought here, instead of being settled on a tiny island shut in by salt water!

Gibbes had been kneeling in the dirt, his stolid face red from excitement and the unaccustomed effort of trying to express himself by signs. Suddenly he leaped to his feet, the mouldy remnants of a fish skeleton in his hands.

"Tom," he exclaimed, "I do believe these benighted heathens are real farmers. Look! They must fertilize with dead fish; there's a skeleton in every hill of this turkey-wheat."

Tom laughed. "As I live, the savages think you're hungry! See, they wish us to go to their huts."

John Gibbes was still looking back over his shoulder as the Indians led them away. Bearskin mats were spread before the largest hut, and as they sat down, an old squaw brought bark slabs on which lay sizzling hot venison steaks. Smaller dishes contained fish, potatoes, a mixture of beans and corn, and fresh berries. The white men, sitting cross-legged like their hosts, gorged themselves until they could eat no more.

"Well, friend Gibbes," said Tom at last, "what think you of this land of Croatan?"

"If I could but find a way, I'd move here tomorrow."

"Would Molly come?"

"She goes where I go, and gladly, too."[Pg 57]

"Yes," said Tom thoughtfully, "and Granny Desmond would come. If Mistress Dare would listen to us, mayhap some of the fools who now think of naught but England could be persuaded, too...."

It was mid-afternoon when they again reached Roanoke Island. It had been a hard crossing, for even on the inland side of the island there had been a nasty little cross-chop to the waves, and an uneasy swell on the normally placid water. As they beached the dugout and pulled it up to its hiding place, Tom noted a thin, thread-like V-line of geese winging its way southward. The coming of the geese meant that storm or cold, or both, were on the way.

As they approached the settlement, a man's voice, frantic with excitement, carried to them.

"A ship! A ship! At last a ship!"

Tom stopped, felt John Gibbes stop behind him, and for a brief space stood perfectly still. The rattling hammer of a woodpecker seemed unnaturally loud. Then, again, came a joyous shout.

"She's heaving to! She's heaving to!"

On the dead run, they broke into the clearing, to see a knot of colonists gathered on the beach, staring out to sea. Sure enough, there was a ship out there, a great, war-rigged ship with furling sails. The sun winked from the brass culverins on her main deck,[Pg 58] and the polished rail on the poop. But the flag restlessly snapping in the rising wind was the red and yellow banner of Spain!

Tom knocked softly on the door of the hut.

"Who is there?"

"Tom Weston."

"Come in."

Tom stooped to enter, and dropped the deerskin covering in place behind him. Eleanor Dare was sitting before the fire, with the baby on her lap. The child stretched its arms toward Tom, and gurgled. There was a muffled shouting from those gathered on the beach. Eleanor Dare spoke almost gaily.

"Well, Mr. Weston, which shall it be now: more colonists to hunt for, or a return to England?"

"Neither, I think," Tom said bluntly. "That ship flies the Spanish flag."

Eleanor Dare looked searchingly at him, and then glanced down at her baby. For a moment she was silent.

"I can only suspect what that means," she said at last. "But I think a Spanish ship would not dare approach an English colony unless something were amiss."

"I'll not be a prisoner of Spain, Mistress," Tom said hotly.[Pg 59]

"No more will I," was the cool reply. "But what can we do? This little settlement is helpless."

"John Gibbes and I have just returned from a land across the water—the place that your father called Croatan. There is safety there for us. If I send Granny Desmond and Molly Gibbes here to you, will you take all the guns and whatever else you can carry, and meet John Gibbes at the north path? He knows where my canoe is. Hold it in readiness. If the Spaniards mean trouble, John will take you to the place we found yesterday, where friendly savages will give you shelter. Will you trust us?"

"I trust you," Eleanor Dare said. "But what of yourself?"

"I propose to talk with the others; perchance I can persuade them to hide on the island until the Spaniards go."

Tom stepped from the hut and walked slowly down to the beach. Granny Desmond hobbled to his side and spoke soberly in his ear.

"What d'ye make of it, Tom?"

"Little enough, Granny. Take Molly Gibbes and go to Mistress Dare's. She will tell you what's to be done."

The waves were crashing up on the beach now, showing their white teeth and falling back again like angry dogs. Tom walked up to Simon Fernando. The big, bearded man looked at him with malice.[Pg 60]

"So," he said, "the Adam of our little island paradise! I regret you have no Eve to stay with you, Master Weston. Naturally, one who loves this place so much will not choose to leave it, eh?"

"Fernando, listen to me."

"Listen to you! For more than a twelvemonth we have heard you sing the praises of this Roanoke. Sing them to yourself henceforth, and be damned to you!"

Tom mastered his temper with difficulty. "That's a Spanish ship," he said loudly, for all to hear. "Who knows whether it comes in peace or war? Better to hide until we are sure, than be prisoners of the Papist Dons."

Simon Fernando lashed out with his fist and caught Tom a tremendous blow on the cheek. Tom staggered backward, and tasted the blood that oozed from a cut lip. He looked toward the sea, and saw small boats putting out from the ship.

Without a backward glance he walked toward the forest. At the beginning of the north path he met Eleanor Dare, who carried a gun in her hands.

"You should not be here," he cried fiercely.

"I am not accustomed to being ordered about, Mr. Weston," she said with composure. "And, if need be, two can fight better than one. Granny Desmond and Molly are watching my babe, and I have been watching you. Your venture met with ill success, I fear."

The ship's boats touched land, and the murmur of[Pg 61] many voices came from the beach. A voice spoke loudly and authoritatively in Spanish.

"He called them English pigs and commanded them to silence," Eleanor Dare translated in a whisper. Her eyes flashed. "Spain and England are at war, and he says their great armada has already destroyed the English fleet. He lies, the rogue! Hawkins and Drake and Raleigh defeated by those lisping lapdogs? Never!"

They slipped back into the forest as a detachment of Spanish marines marched up toward the settlement and began to attack the huts with the colonists' own mattocks and adzes. There came the sound of rending bark and falling timbers. A man yelled. Another voice—a strangely familiar one—spoke in Spanish. There was a reply in the same tongue.

"That was Simon Fernando!" Eleanor Dare said contemptuously. "He said others remained on the island, and was told they could starve here. The ship must get off ere the storm strikes."

An hour later, when they dared come out of their hiding place, they found the huts in ruins and the beach deserted. The Spanish ship was already a spread of white sails putting out to sea. As they watched, a powerful gust of wind swept across her, and she heeled dangerously.[Pg 62]

"There goes my lord Raleigh's second venture," said Eleanor Dare sadly. "Would you still have us go, too?"

"We must wait for the storm to pass," Tom replied, "and gather whate'er we can from these ruins. Next time, the Spaniards will not find us so easily."

"True, Mr. Weston." Eleanor Dare's eyes were clouded. "But could an English ship find us, either? God send there may be one, some day."

Tom looked to the westward, the unbounded land where there were none but them to carry Raleigh's dream.

"I can promise only this," he said gently. "There will be some to follow us, and we can point the way."

He stepped to a tree and with the point of his knife carved one word:

CROATAN

The beginning of the Seventeenth Century saw the French firmly established on the St. Lawrence. Shrewd Breton and Norman merchants had realized that if New World fish furnished a livelihood for their grandfathers, New World furs would provide a fortune for themselves, under the guiding hand of the great Champlain. In 1611 they built an advance trading post where Montreal now stands, for it was here that the Ottawa River emptied its waters into the mighty St. Lawrence. The Ottawa was the highway of the fur-trading Hurons, who lived on the shores of the great inland seas of Georgian Bay and Lake Huron.

If furs could come down the river, faith could go up. France not only wanted furs, but she was eager to give Christianity as well as trade goods for them. So the Ottawa became as familiar to missionaries as to merchants. In fact, the first white man to make the arduous and dangerous trip to Lake Huron was neither a trader nor a soldier, but a humble priest whose zeal lighted a path for more famous men to follow—Father Joseph LeCaron.

Father LeCaron rose from his knees and stood looking down at the covered form of the dead Huron. He had saved his first soul from pagan savagery and committed it to God's mercy. In this strange, wild country of New France, it was a comfort to know that in his last extremity, deserted by all his fellows, one simple savage had listened to and believed the Truth. The priest uttered a final prayer over the body of the Huron, then gathered his gray robe about him to walk through the long lodge—a building so cunningly joined and covered with bark that neither wind nor rain nor snow could penetrate it.

The other Indians in the lodge looked respectfully at him as he walked by. But Joseph LeCaron's mind and thoughts were still occupied with the dead warrior whom he had comforted throughout the night. Yesterday morning the warrior had been borne down the river to the village by six of his fellows, and left in the priest's care. Father LeCaron tried to tell himself that they had done so because they loved and respected the word of God. But in his heart he knew that none had wanted to bother with the wounded man, who, as anyone could see, was as good as dead.

The savages had been much more interested in the two Iroquois scalps which the war party had also brought. In a most heathenish and unseemly manner they had exulted over their grisly trophies. Indeed,[Pg 66] the whole Indian village had joined the wild party that celebrated both the killing of the Iroquois and the arrival of Samuel de Champlain, who was going to help them fight their mortal enemies. The savages' was an un-Christian faith, so far removed from the True Belief that, in moments of extreme discouragement, Father LeCaron had wondered if they would ever be converted. His heart sat heavily within him. His task seemed too great.