Some time before his death, Sir Wilfrid Laurier placed in my hands all his papers, covering the period to the close of his term of office. After his death, Lady Laurier gave access to the later papers. These papers included all the documents of public interest which he had accumulated, with the exception of a few boxes of letters lost in the burning of the Parliament Buildings during the war.

It will be noted that few letters have been reprinted in the early as compared with the late years of Sir Wilfrid's life. There is a striking difference, in the character of the correspondence of the middle and of the last years. During his years of office, when business pressed and when men came across a continent at a prime minister's nod, the letters, though abundant, are nearly always brief and rarely of general interest. In the years of comparative leisure, when a leader in opposition had to go to men, or write them, and particularly when emotions were stirred, the letters are longer and freer. Sir Wilfrid's caution and his remarkable memory lessened the extent to which he committed himself on paper. He never wrote a letter when he could hold a conversation, and he never filed a document when he could store the fact in his memory: fortunately, his secretaries saw to the filing. So far as is known, he never wrote a line in a diary in his life. He was not given to introspection; he lived in his day's work.

The writer is deeply indebted to friends of Sir Wilfrid and of his own who have read these pages in proof. They are given to the public with the hope that they may provide his countrymen with the material for a fuller understanding of one who was not only a moving orator, a skilled parliamentarian, a courageous party leader, and a faithful servant of his country, but who was the finest and simplest gentleman, the noblest and most unselfish man, it has ever been my good fortune to know.

O. D. Skelton.

Kingston, Canada,

October, 1921.

| chapter | page | ||

| I | The Making of a Canadian | 3 | |

| II | The Political Scene | 45 | |

| III | First Years in Parliament | 105 | |

| IV | The Mackenzie Administration | 157 | |

| V | Under a New Leader | 218 | |

| VI | Rail and Riel | 260 | |

| VII | Leader of the Liberal Party | 332 | |

| VIII | Market, Flag, and Creed | 350 | |

| IX | The Break-up of the Administration | 424 |

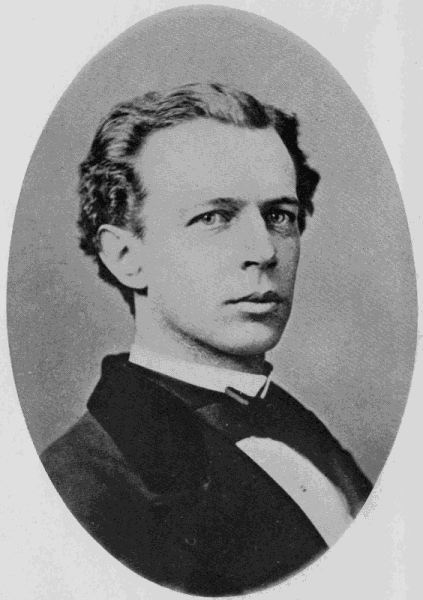

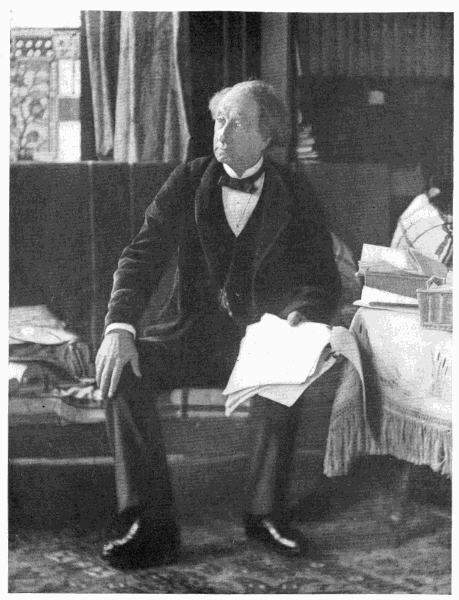

| Wilfrid Laurier | Frontispiece |

| facing page | |

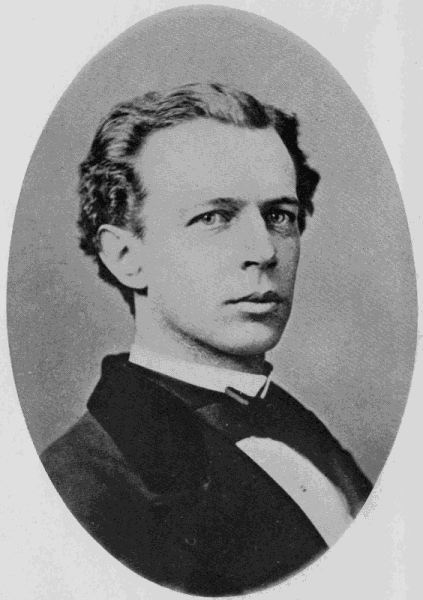

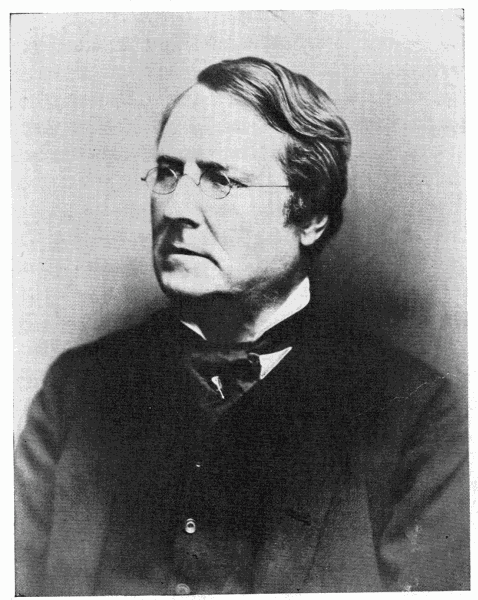

| Carolus Laurier | 20 |

| River Achigan and St. Lin | 28 |

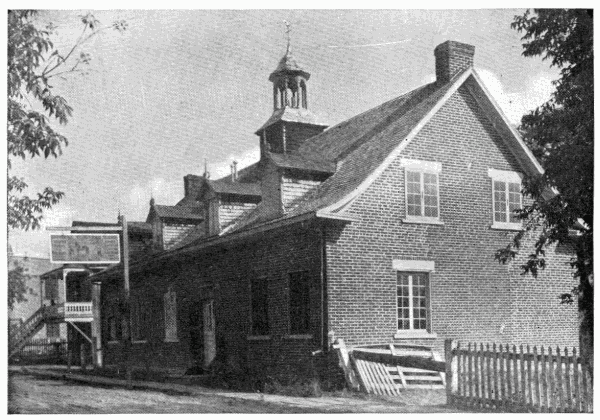

| The Village School, St. Lin | 32 |

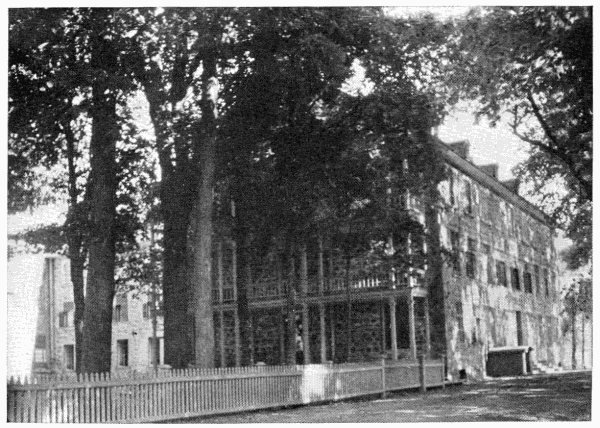

| L'Assomption College | 32 |

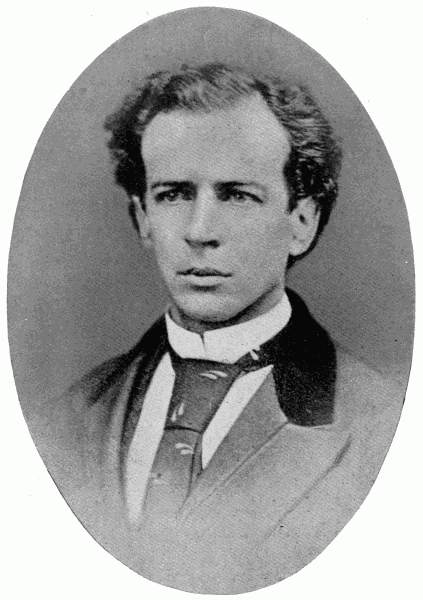

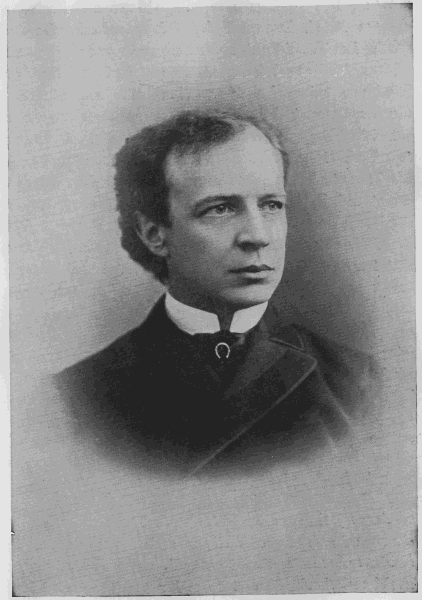

| Wilfrid Laurier | 40 |

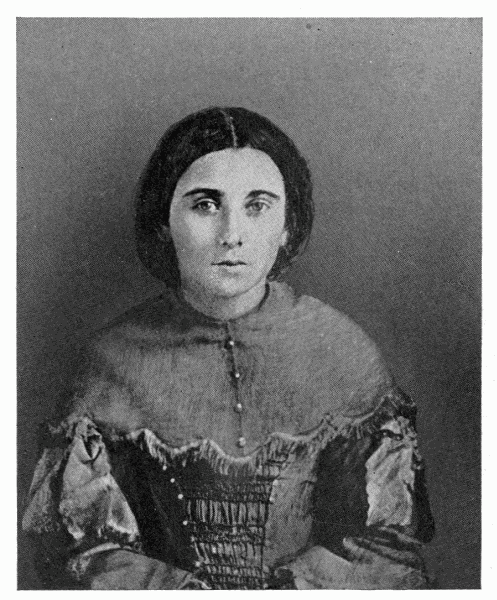

| Mlle. Zoë Lafontaine | 48 |

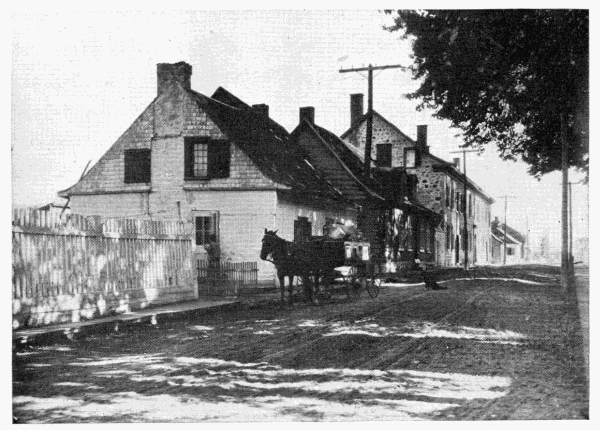

| A Street in L'Assomption | 64 |

| The Hills of Arthabaska | 64 |

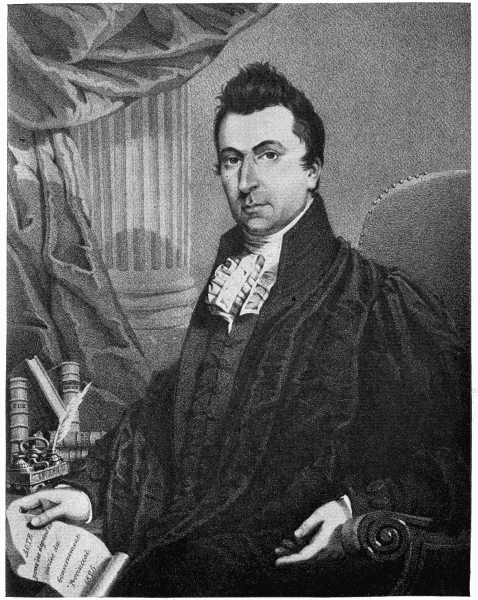

| Louis Joseph Papineau | 80 |

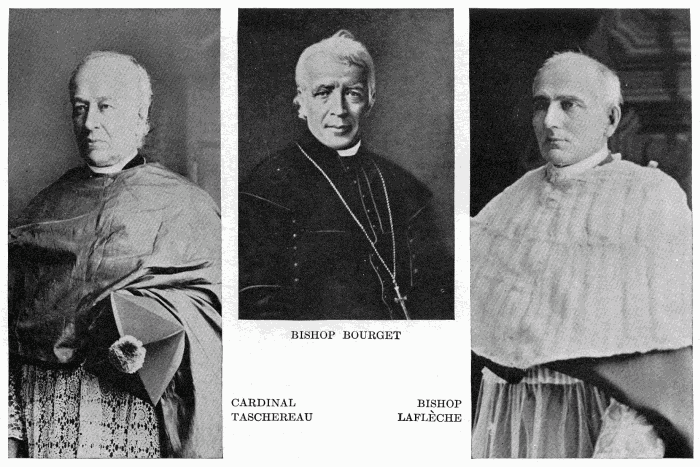

| Cardinal Taschereau | 128 |

| Bishop Bourget | 128 |

| Bishop Laflèche | 128 |

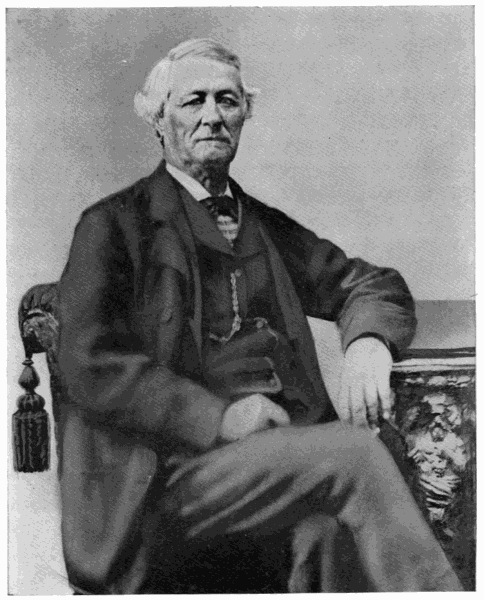

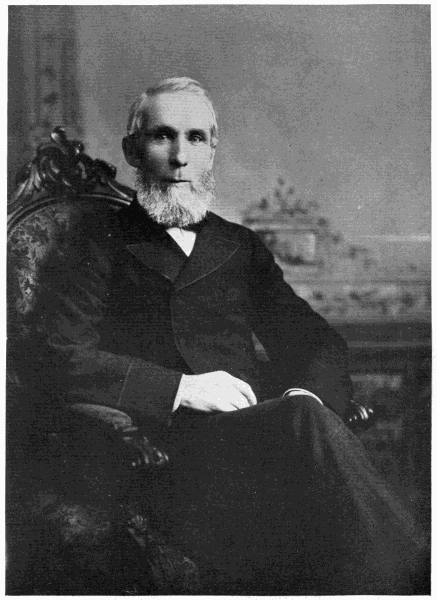

| Alexander Mackenzie | 160 |

| Edward Blake | 224 |

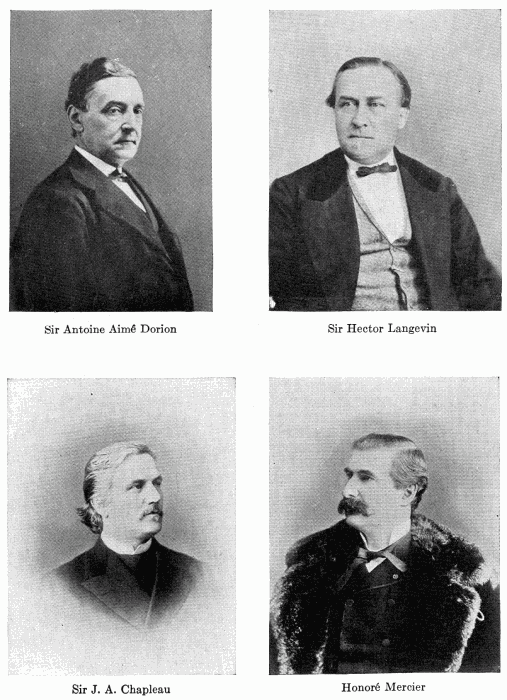

| Four Quebec Leaders | 240 |

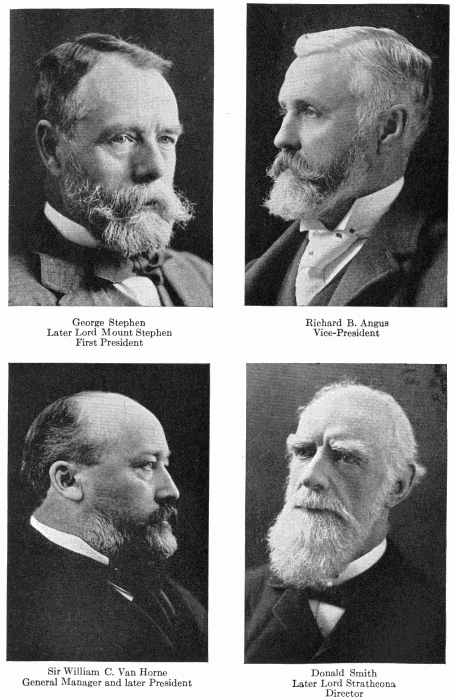

| Builders of the Canadian Pacific | 272 |

| Wilfrid Laurier | 336 |

| Sir John A. Macdonald | 416 |

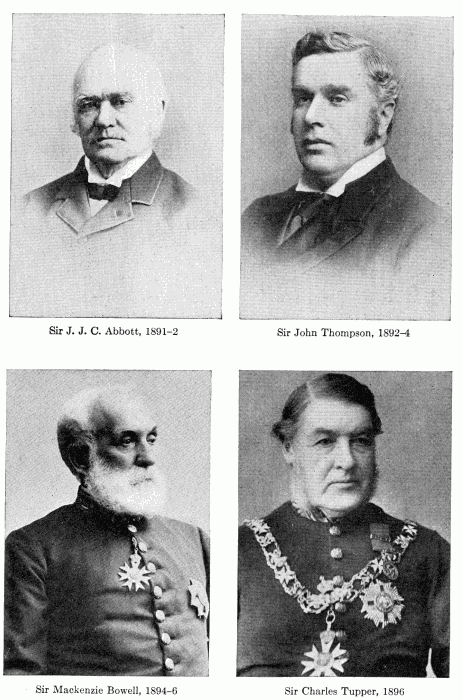

| Four Conservative Prime Ministers | 464 |

The Peopling of New France—An Outpost of the Faith—A Soldier of France—The Laurier Stock—The Habitant—New France and British Policy—Charles Laurier, Inventor—Carolus and Marcelle Laurier—Birth of Wilfrid Laurier—Boyhood in St. Lin—An English Schooling—L'Assomption College—Student at Law—Early Partnerships—The Eastern Townships—A Happy Marriage.

WILFRID LAURIER was born at St. Lin, a little village on the Laurentian plain north of Montreal, on November 20, 1841. Exactly two hundred years earlier his first Canadian ancestor had fared forth from Normandy, a member of the little band of pioneers who had undertaken to plant an outpost of France and the Faith on the Iroquois-harried island of Montreal. For eight generations his forefathers took their part in the unending task of subduing the Laurentian wilderness. Striking deep roots in Canadian soil, shaping and shaped by the new ways and new interests of the colony, they worked, like thousands of their compatriots, for the most part in obscurity and silence. Then at last the sound and sturdy stock[4] found expression. We cannot understand Wilfrid Laurier, his character, temperament, viewpoint, his problems, limitations, achievements, unless we bear in mind those two centuries of life and work in the Canada which had become his kinsmen's only home.

France had entered late into the race for overseas possessions. The wars of religion, entanglements in Europe, court intrigues, had occupied the whole interest of her rulers. When at last, in the seventeenth century, with a measure of unity attained at home, France had brief leisure to dream of New-World empire, there seemed little place left in the sun. Spaniards and Portuguese, English and Dutch, were staking out the lands of sun and gold. French adventurers found a footing in India and Florida and Brazil, but for the most part they followed the track of Breton fishermen to the fogs and furs of the St. Lawrence. In 1608, a year after the London Company had founded, in the marshes of Jamestown, the first enduring English settlement in the South, Champlain founded, on the rock of Quebec, the first enduring French settlement in the North. For all Champlain's courage and persistence, it grew but slowly. The weary and perilous voyage in crude and comfortless craft barred all but the most courageous or the most despairing. There was no gold to lure. The fur-trade was monopolized by the trading companies to which in turn kingly favour inclined. It was a task of years to clear an opening in the dense forests, and the little settlement planted in a vast fertile continent was long dependent for food and stores on the yearly ships from[5] France. The Iroquois lurked at the gate. Winter and scurvy and brandy played havoc with men who would not learn the country's ways. If New France was to become more than a fur-trader's post, some other power was needed to drive or draw men forth.

That power was religion. In the English settlements to the south, it was religion more than any other factor that impelled men to leave the land of their birth and seek homes overseas. Men who could not find in England freedom to worship as their conscience dictated, or power to make others worship as they themselves pleased—Puritans, Quakers, Roman Catholics, and, in Long Parliament days, Episcopalians—formed the backbone of the settlements on the Atlantic coast, and gave the young colonies their fateful bias toward self-government.

In New France it was not the discontent of a religious minority that sent men and women overseas. This solution of France's colonizing problem had been definitely rejected. France, like England, had its dissenters: there were in Europe no more resolute or enterprising men, no better stuff for the building of a new state, than the Huguenots. But they were not allowed to find an outlet in America, under the flag of France. For years advisers of the court, lay and cleric, urged that New France should be saved from the evil of a divided faith which had brought old France to the verge of ruin, and that the simplest way to avoid conflict was to bar the Huguenot. Insistent pressure and the flaring out again of Huguenot revolt, brought Richelieu to yield, and in[6] the charter granted the Hundred Associates trading company, in 1627, all Huguenots and foreigners were forbidden to enter the colony. The discontented minority who might have emigrated to New France and who eventually were exiled from France to build up her rivals, were not allowed to grapple with the task. The contented majority for whom the colony was reserved had little wish to go.

Yet in another way than in the English colonies religion was destined to provide the impelling force. There were among the Catholics of France men and women of burning zeal, who felt a call to bring the Indians to Christ. While English settlers with their families were flocking to New England and Virginia, seeking to better themselves both here and hereafter, in New France martyr priests and devoted nuns were facing endless perils and privations in the hope of winning savage souls. There are no more glorious pages in the annals of missions than those which record the womanly tenderness and practical efficiency of Jeanne Mance and Marguerite Bourgeoys and Mère Marie de l'Incarnation, or the devotion of Franciscan and Jesuit fathers, Le Caron and Dablon, Lalemant and Brébeuf, Le Jeune and Massé and Jogues, following the shifting, shiftless Montagnais through filth and famine, labouring patient years in the great Huron villages of what is now western Ontario, or braving the Iroquois in their innermost strongholds, only too often crowning a life of service by martyrdom under the scalping-knife or at the stake.[7]

The reports or Relations in which each year the Jesuits recorded their efforts, fired the imagination of pious men and women throughout France. Not least they stirred one extraordinary group of men and women, in whom mystic piety, hard-headed grasp of practical affairs and unquestioning courage were strangely mingled, to a resolve to plant the Cross far toward the heart of the new land. Jerôme le Royer de la Dauversière, tax-gatherer of Anjou; Jean Jacques Olier, Paris abbé and later founder of the Order of St. Sulpice; Pierre Chevrier, Baron de Fancamp; Mme. de Bullion, as pious as she was rich; Mlle. Jeanne Mance, honoured of all Canadian nurses who have followed in her footsteps, and Paul de Chomedy, Sieur de Maisonneuve, Christian gentleman, whose simple faith had withstood contact with soldiers and with heretics, were only the more notable of the associates who thus came together to found the Society of Our Lady of Montreal. Their aim was to found a mission outpost on the island of Montreal, which lay at the junction of the two great Indian waterways, the St. Lawrence and the Ottawa, and was famed through all North America as a rendezvous. Here priests were to minister to the spiritual needs of such savages as could be made to halt and heed; nursing sisters were to care for the sick and the aged, and teaching sisters to instruct the young. Funds were raised, a grant of the island secured, soldier colonists selected, and three small vessels equipped. In the summer of 1641 the expedition reached Quebec. Here they found little backing for their rash venture. Gov[8]ernor and Jesuit sought to dissuade them from inevitable and useless sacrifice; it was unwise to scatter forces when the whole white population of Canada was less than three hundred; the island of Montreal was straight in the track of the Iroquois hordes who every year swept up the St. Lawrence and the Ottawa in their relentless hunting of men. But Maisonneuve insisted that to Montreal he would go "if every tree on the island were to be changed to an Iroquois," and in the following spring the undaunted little band took possession.

Among the soldier colonists who followed Maisonneuve there was found Wilfrid Laurier's first known Canadian ancestor. [1] Augustin Hébert was a native of the Norman town of Caen, the birthplace of William the Conqueror. Four years after his coming he married a girl of twenty, Adrienne Du Vivier, daughter of Antoine Du Vivier and Catherine Journé, originally from Carbony, in the province of Laon. Four children were born to them, Paule, Jeanne, Léger, and Ignace. Paule, who died in infancy, was sponsored by M. de Maisonneuve and Mlle. Mance. In August, 1651, Augustin Hébert died of wounds received in an engagement with the Iroquois. Three years later his widow married Robert Le Cavelier. M. de Maisonneuve granted them forty arpents of land near the fort, on condition that the land might be resumed if needed for building, that Adrienne Du Vivier renounced her dowry and her rights in the estate of her first husband, and that they would undertake to bring up the three surviving children of Hébert until they attained their twelfth year. [2]

[9]The vision of Indians flocking peaceably from all the St. Lawrence valley to hear the gospel message faded before the stern reality of Iroquois attack. The Five Nations had vowed to destroy the whole French colony, and particularly the outpost at Montreal. They were then at the height of their power. An unusual capacity for political organization, a shrewd mastery of diplomacy, a grasp of military strategy, a persistence as rare among Indians as their ruthlessness was common, and, not least, ample stores of firearms sold by recklessly profiteering Dutch traders from New Netherlands made the Iroquois the most formidable of all Indian peoples, unquestioned lords from Maine to the Mississippi and from Hudson Bay to Tennessee. Hurons, Neutrals, Eries, Andastes, in turn were exterminated. Only their French foes withstood them. For twenty-seven years (1640-67) the war continued, with only two brief breathing spells. Now great bands of warriors attacked in force; now single braves lurked for days in ambush to catch a Frenchman unawares. The builders of this New Jerusalem, as of the Jerusalem of old, worked in [10]the fields with their weapons by their side. "Not a month of this summer passed," a chronicler recorded, "but the book of the dead was marked in letters of red by the hand of the Iroquois." Maisonneuve and his comrades fought hard, worked hard, prayed hard, and against all chance the little colony survived. Rarely had they strength to take the offensive. One breathing spell came when in 1660 Adam Dollard and his immortal sixteen young comrades, all but two in their twenties, after making their wills, their peace with their Maker, and their last farewells, struck up the Ottawa to meet the oncoming Iroquois, and at the Rapids of the Long Sault, Canada's more glorious Thermopylæ, fought for eight days and nights against seven hundred frantic foes, until arms, water, strength but never courage failed, and one by one the little band had fallen by musket or tomahawk or at the stake.

Exploits such as Dollard's checked the Iroquois, but only a great accession of force to the colonists could subdue them. Fortunately help was at hand. The rulers of France had at last both the will and the power to aid. The young king, Louis XIV, and his great minister, Colbert, were for the moment keenly alive to the possibilities of colonial strength. The Hundred Associates, the trading company which for a generation had misruled New France, lost its charter, and in 1663 the colony came virtually under the king's direct control. Jean Talon, intendant or business manager of the colony, came out to play Colbert's part on the smaller stage. Soldiers and settlers streamed in for a decade,[11] and the Marquis de Tracy, at the head of large French and Canadian forces, laid waste the Iroquois country and brought peace for a score of years.

One of the soldiers in Tracy's crack force, the regiment of Carignan-Salières, raised by the Prince de Carignan in Savoy, tried and hardened in campaigns against the Turk, and brought to Canada under Sieur de Salières, was François Cottineau, dit Champlaurier, the first of the Laurier name in Canada. François Cottineau was born in 1641 at St.-Cloud, near Rochefoucauld, in what was then the province of Angoumois and is now the department of Charente, son, as the records say, of Jean Cottineau, vine-grower, and Jeanne Dupuy. In that day, when family names were still in the making, doubtless some ancestral field of lauriers or oleanders had given a sept of the Cottineaus the additional surname which in time was to become their only one.

The coming of Talon and Tracy assured the permanence of the colony. The little settlement on the island of Montreal shared in the brief outburst of vigour and support. Its religious purpose was not forgotten. Priests of the Order of St. Sulpice took spiritual charge and temporal lordship of the island, not without a bitter feud with the Jesuits which did not soon die. Mlle. Mance still gave to the Hotel Dieu her skill and judgment, and Marguerite Bourgeoys continued the work of teaching which the Congregation de Notre Dame has carried on to this day. But gradually the advantages of the island port for trade, and the rich farming possibilities of the volcanic island soil, led to growth in other[12] directions which soon overshadowed the original activities of the associates of Our Lady of Montreal. Montreal, like all New France, had ceased to be merely a fur-traders' counter and a missionaries' base of operations; it had become for all time a land of settlers and of homes.

For a few brief years the State took unwonted care to stimulate the growth of New France. Officers and men of the Carignan-Salières regiment were induced to settle, Roman-wise, on the imperilled borders, though it is to be feared that more of them turned coureurs de bois, roaming far in the Western wilderness, than remained to till the soil of the Richelieu seigniories. Ship after ship of settlers came, and thrifty efforts were made to save the men of France for cannon fodder in Europe by encouraging early marriage in the colony itself. Hundreds of girls were brought from the old land, and married out of hand to soldier and settler. The quick to wed were rewarded and the tardy punished. The State provided dowries of money or supplies, while in anticipation of Honoré Mercier, Louis XIV offered a pension of three hundred livres to all Canadians who had ten children living and four hundred for families of twelve—girls who had entered any religious order not being counted. Fathers were fined if their sons were not married at twenty or their daughters at sixteen, and marriageable bachelors were forbidden to set out hunting unless they undertook to marry within a fortnight of the arrival of the next matrimonial ship from France. [3] Not [13]even a Colbert could ensure that such drastic and paternal interference would be permanent, but pressure of Church and State and frontier conditions long made marriage at an early age a feature of New France.

This rapid marrying and the steady pushing back of the frontier which went with it, are brought out clearly in the annals of the Hébert and the Cottineau-Laurier families. Thanks to the care with which the parish registers were kept by the church authorities, and the tireless industry with which historians from Abbé Tanguay to M. Massicotte have delved into the records, and thanks also to the fact that immigration from France ceased early, making it possible to trace all the present families to the early stocks, we can follow the branching of these, as of countless other families of New France, without a break through the generations.

Jeanne Hébert, the only surviving daughter of Augustin Hébert and Adrienne Du Vivier, was married in Montreal in 1660, to Jacques Millot, son of Gabriel Millot and Julienne Phelippot; the bride was in her fourteenth year, but the husband, doubtless a newcomer, in his twenty-eighth. They did not quite earn the[14] King's pension, for though they had ten children, not more than seven were living at one time. It was the eldest of these ten children, Madeleine Millot, who in 1677 in her fifteenth year, was married to the soldier of Carignan-Salières, François Cottineau, dit Champlaurier, then approaching thirty-six.

Marriages in those days might be made early, but they were not contracted lightly. The marriage contract of François Cottineau and Madeleine Millot, which is still preserved, reveals with what a multitude of witnesses—kinsmen, neighbours, old regimental officers—the solemn undertaking was made, and with what thrifty and cautious care the future family finances were detailed and guarded. [4]

When the eldest of the four children of François Cottineau-Laurier, fittingly named Jean Baptiste, was married at twenty-six to Catherine Lamoureux, a girl of sixteen, youngest but one of a family of eleven, it was not at Montreal but at St. François in Ile Jésus, to the northeastward, that the marriage was performed. That even Colbert could not mould the people to his will is made clear by the fact that the two daughters of François Cottineau-Laurier did not marry until one was twenty-nine and the other was twenty-four. Jean Baptiste made his home at Lachenaie, across the river from St. François, but at first in the same parish. Here his quiverful of children were born—Jean Baptiste, Marie Catherine, Marie, Agathe, Jacques, Rose, Thérèse, Joseph, Pierre, Marie Anne, and Véronique.

[15]Here it was, in 1742, that Jacques, his second son, at twenty-six, married Agathe Rochon, aged twenty-one, and here for three generations more the family took root.

In every parish from Tadoussac to Montreal the same story of early and fruitful marriage and of steady widening of the bounds of settlement is to be told. All along the St. Lawrence and the Richelieu the habitants were clearing their deep narrow holdings, winning an acre or two a year from the dense forest. Facing the river-road, the steep-roofed whitewashed houses of logs or field stone, a furlong apart, soon gave the river bank the air of an unending village street. Fur-trader and explorer, missionary and soldier, ventured far into the unknown West; while the English colonists were still clinging to the coast or breaking through the Appalachian barrier, the sons of New France were blazing trails from Texas to Hudson Bay and from the Atlantic to the foothills of the Rockies. Yet the great bulk of the population remained in the St. Lawrence valley, and in that community farming more and more became the mainstay.

Farming methods were crude, but the soil was rich and the habitant hard-working. Save in a rare famine year, he had in his fields abundance of wheat and oats, of corn and rye and the indispensable peas, and of fish and game and wild fruits in the river and forest at his door. Home-brewed ale and, later, home-grown and home-cured tabac canadien helped to pass the long winter nights. Every household was self-sufficient and self-contained. The habitant picked up something of many[16] a trade, and developed a versatility which marks his descendants to this day. From the iron-tipped wooden plough, the wooden harrow and shovel and rake, to the spinning-wheel that stood beside the great open fire-place, the many-colored rug, the homespun linens and étoffe du pays, the wooden dishes, the deerskin moccasin, the knitted tasselled toque and the gay sash, all were his own and his family's handiwork.

The habitant had found comfort. He had not yet found full freedom, though the independent strain in his blood and the democracy of the frontier ensured him much greater liberty than is usually recognized, and there was always the safety-valve of escape to the lawless life of the coureur de bois. In the wider affairs of the colony he had little voice. King and governor and intendant made his laws, with some slight aid from a nominated council; yet his taxes were light, and if he did not make the laws, neither did they greatly circumscribe his daily life. The seigneur counted for more in his eyes than the king, but had only a shadow of the authority wielded by feudal lords in France: the farmer proudly insisted that he was habitant, not censitaire. The Church came closest. The missionary aims of the founders of the colony, the unwearied devotion of the Church's servants, the outstanding ability of some of its servants, notably Bishop Laval—America's first prohibitionist—and the barring of heretics, gave the Church sweeping and for a time unquestioned and ungrudged authority. After Colbert came to office, and throughout the French régime, the State increasingly[17] asserted its power, controlling the Church in matters of tithes, the founding of new orders or communities, appeals from ecclesiastical courts, and many issues of policy, but the Church remained the dominant social influence in the colony.

Already New France had taken on a life and colour of its own. Governors and merchants and soldiers might come and go, but the ways of the colony were little changed. The striking and significant feature of these later years is the cessation of contact with France through immigration. The outburst of colonizing energy under Colbert proved brief. Louis XIV and Louis XV were seeking glory on European battle-fields, and could spare no men for the wilderness. Daring projects of American empire were staked out, but the men needed to hold and develop the vast arc from Montreal to New Orleans did not come. In the seventy years up to 1680 the colony had received at most three thousand immigrants from France; in the eighty years that followed, an incredibly small number came—a number which a distinguished authority, M. Benjamin Sulte, has put as low as one thousand all told. Through all this period France had more than twice the population of the British Isles, but did not send one settler to the New World for the twenty that Britain and Ireland urged and forced to go. In forty years half the Presbyterian population of Ulster sought refuge in the American colonies from British industrial and religious oppression; German, Dutch, Swiss settlers poured in during the eighteenth century by tens of thou[18]sands. The numbers of Ulstermen and of Germans coming to the English colonies in a single year exceeded the number of French settlers who crossed the Atlantic in the century and a half from the beginning to the end of the French régime. Of the four or five hundred thousand Huguenots exiled from France more came to the English colonies than Catholic France could spare for her own New-World plantations, and the names of Bowdoin, Faneuil, Revere, Bayard, Jay, Maury, Marion, and many another bear witness of their quality. For all the rapid multiplying of the original stock in New France, it continued to be outnumbered by the English colonies twenty to one.

For New France this cessation of new settlement and the limitation of growth to the natural increase of population, meant isolation and the development of a distinctive, homogeneous community. With each year that passed the men of New France knew less of any country other than the land of their birth. For old France it meant defeat in the struggle for colonial empire, defeat which might be postponed by the bravery and resource of individual leaders, by the firm military organization of the people of New France, and by the disunion of the English colonies, but which could not be averted.

The French régime came to an end a century and a half after Champlain had raised the flag of France on the rock of Quebec. The new rulers were faced at once by the most serious difficulty that had yet beset any colonizing power. Here were nearly eighty thousand Frenchmen and Catholics, firmly rooted in the soil, with[19] ways of life and thought fixed by generations of tradition. What was to be the attitude of their English and Protestant rulers? On the answer to that question hung the future of Canada, and the answer, or rather the answers, that were given shaped the problems and the tasks that in after days faced Wilfrid Laurier and his contemporaries and that in changing forms will face the Canadians of to-morrow.

The solution first adopted was what might have been expected in a time when the right of self-determination had not even become a paper phrase. It was simply to turn New France into another New England, to swamp the old inhabitants by immigration from the colonies to the south and to make over their laws, land tenure, and religion on English models. No little progress had been made in this attempt when the shadow of the American Revolution and the sympathy of soldier governors for the old autocratic régime and for the French-Canadian people about them brought a fateful change in policy. British statesmen determined to build up on the St. Lawrence a bulwark against democracy and a base of operations against the Southern colonies in case of war, by confirming the habitant in his laws, the seigneur in his dues, the priest in his authority. To keep the colony British, the government now sought to prevent it becoming English. The Quebec Act, the "sacred charter" of French-speaking Canada, embodied this new policy. A measure of success followed. Then the unexpected result of the American Revolution in exiling to the St. Lawrence and the St. John tens of thousands[20] of English-speaking settlers made it impossible to keep Canada wholly French, and the hatred for democracy and for all things French which developed during the wars with Napoleon made Englishmen unwilling to let French-speaking Canada rule itself.

The lesson which the statesmen in control in Britain learned from the two revolutions, the American and the French, was not the need of making terms with democracy, but the need of nipping democracy in the bud. Elective assemblies were conceded the people of Lower or French-speaking Canada, and Upper Canada, the newer English-speaking settlements to the west, as they had previously been granted to the old colony of Nova Scotia and the Loyalist settlement of New Brunswick, but beyond this British governments would not go. An all-guiding Colonial Office, a governor who really governed, an appointed, and but for the grace of God an hereditary, upper house which could always block the popular assembly, little cliques of a governing caste in control of administration, a church established and endowed to teach the people respect for authority, long barred the advance of self-government. Then the tide of democracy surging through the world, the constitutional campaigns of Baldwin and Papineau and Howe, the bullets of Mackenzie's and Chenier's men, the abandonment by Britain itself of the protectionist ideal of a self-contained empire, forced reform. This is not the place to repeat the familiar story of that early struggle for self-government. Later it will be necessary to consider what were the results of the [21]half-century of British policy and Canadian development, on the political and party situation, the unity of the provinces, the relations of Church and State, the sentiment of French-Canadian nationalism, the evolution of the colonial status, and the other issues which faced Wilfrid Laurier and his fellow-countrymen as they came to manhood.

While these affairs of state were in the balance, generation after generation of Lauriers were hewing their way through the Northern woods. It was in 1742 in the parish of Lachenaie that Jacques, second son of Jean Baptiste Laurier and Catherine Lamoureux, married Agathe Rochon. Charles Laurier, fourth of Jacques's five children, was a boy of eleven when the battles of the Plains of Abraham and of Ste. Foye were fought. In the year of the Quebec Act he married Marie Marguerite Parant, or Parent. Of their four children, only two, Charles and Toussaint, grew to manhood. With Charles Laurier the younger the capacity of the stock began to reveal itself and the environment to take the shape required to fit his grandson, Wilfrid Laurier, for the part he was to play in his country's life.

Charles Laurier, the grandfather of Wilfrid Laurier, was a man of unusual mental capacity and force of character. His interests and ambitions extended beyond the narrow range of habitant life. Not content with the scanty education available in the parish school, he mastered mathematics and land-surveying. He surveyed a great part of the old seigniory of Lachenaie, originally granted to Sieur de Repentigny in 1647, and later di[22]vided, the western half, two leagues along the river and six leagues deep, falling in 1794 into the hands of Peter Pangman, "Bastonnais" or New Englander, famed for his exploits as fighter and fur-trader in the far North-West.

Charles Laurier had an ingenious and practical turn, which is evidenced by the fact that he was the first man in Upper or Lower Canada to obtain a patent for an invention. In 1822 he invented what he termed a loch terrestre, or "land log." The Quebec "Gazette" of June 24, 1822, noted that an ingenious machine to be attached to the wheel of a carriage for measuring the distance traversed had been exhibited that month in Quebec, and that it was the invention of Mr. Charles de Laurier, dit Cottineau, who intended to seek a patent from the legislature next session. A letter in the "Gazette" a few days later from Charles Laurier himself dealt at length with the device. He explained that the "land log" recorded automatically the number of revolutions of the carriage-wheel to which it was attached, the dials indicating in leagues and decimal fractions of a league the distance traversed. In a carriage to which this instrument had been attached, one could almost make a survey of a province while driving, provided one had a good compass.

In the summer of 1823 M. Laurier determined to put his suggestion into practice. He attached the instrument to the dashboard of a calèche, with five dials indicating respectively tens of leagues, units, tenths, hundredths, and thousandths. He drove from Lachenaie[23] to Quebec city, recording the distance as 54 and 487/1000 leagues. The legislative assembly, after calling Joseph Bouchette, the surveyor-general of the province, and E. D. Wells, a Quebec watchmaker, as expert witnesses, decided to grant the patent. It was not until 1826, by which time five other patents had been registered, that the formalities were completed, the fees paid and the patent obtained. In the same year, 1826, we find him asking the Assembly for assistance in making experiments in measuring distances on water and recording the course of a vessel at sea. No aid was granted, and apparently nothing further came of the project.

In 1805 Charles Laurier married Marie Thérèse Cusson. To his son Charles, or Carolus, who was born in 1815, he gave a forest farm at St. Lin, on the river Achigan, some fifteen miles northeast of Lachenaie. Here the son followed in his father's footsteps, surveying and farming by turns, and here in 1840, when Carolus had been married some six years, Charles and his wife came to spend the rest of their days in a joint household.

The strong common sense of the elder Laurier, his frankness and his sturdy emphasis on independence are brought out clearly in the étrennes or New Year's blessing sent to Carolus in 1836:

(Translation)

New Year's Blessing of Carolus Laurier

January 1st, 1836

My Dear Son:

For New Year's blessing I am going to give you some ad[24]vice, and I hope that you will not scorn it, as you are now the head of a household, a substantial villager, and consequently a member of society.

Now in order to be a good member of society, you must be independent. Besides independence, many rules of conduct are understood, but that is the root of them all. Independence does not always mean riches! It means prudence, foresight in business so that you are not taken unawares and forced to yield or compromise with anyone. You must judge your own business, watch over everything that goes on in your house, in a word, over all that may help or hinder your interests.

You must subdue the flesh. That is to say, work reasonably, prudently and faithfully. A man of bodily activity may earn, without any exaggeration, 25 or 50 dollars a year more than an indolent man would. That may make an increase in his fortune of from 13 to 26 thousand francs at the end of 30 years.

Finally, my son, you are your own master; do as you please; I give you no commands. But if you wish to achieve independence, pray God to direct your thoughts and your work. It is spiritual and bodily activity which leads to independence: the indolent man is always in need. This precept may be of service to your wife and to everyone.

Charles Laurier,

Your affectionate father.

The same Polonian prudence is evident in another New Year's letter, written this time to his daughter-in-law, in anticipation of the two households being joined:

New Year's Blessing of Marcelle Martineau, Wife of

Carolus Laurier

(Translation)

January First, 1840.

Dear Madam:

As we intend to be joined together next year and for the rest of our days, unless we are greatly disappointed, God grant that we may live on good terms with one another. It is to [25]Him that we must pray for this. Be resolute and patient. If we take care, both of us, not to be embittered against one another, we shall be able to live together happily, for it will be less costly to keep house for two families joined together than separated, as regards both household tasks and expense. If we have the good fortune to agree, we shall be happier together than apart. That is why we must fortify ourselves beforehand with prudence and patience and resignation. When we fear some misfortune, it is very seldom that it comes to us. Be wise and prudent.

Charles Laurier.

Carolus Laurier had not the rugged individuality or the practical interests of his father, but he had his own full share of capacity. His keen wit, his genial comradeship, his generous sympathy, his strong, handsome figure, made him a welcome guest through all the French and Scotch settlements of the north country. He was more interested in political affairs than his father had been, and a strong supporter of the Liberal or "Patriot" demand for self-government. It was an index of his progressiveness that he was the first in the countryside to discard the flail for a modern threshing-machine.

It was to his mother that Wilfrid Laurier always felt he owed most. Marie Marcelle Martineau was born in L'Assomption in 1815. Her first Canadian ancestor was Mathurin Martineau, who emigrated to Canada from the same part of France as Jean Cottineau, about 1687; from this Martineau stock came the poet Louis Fréchette, who counted himself a Scotch cousin of Wilfrid Laurier. On her mother's side—Scholastique or Colette Desmarais—Marcel Martineau had the blood of Acadian exiles in her veins. In 1834, when each was[26] nineteen, Carolus Laurier and Marcelle Martineau were married at L'Assomption. Marcelle Laurier was a woman of fine mind and calm strength, with an interest in literature and an appreciation of beauty in nature unusual in her place and time. She was passionately fond of pictures, though there was little opportunity to gratify her longing, and had a very good natural talent for drawing. In the home she made in St. Lin there was an intellectual interest and a grace and distinction of life which were to leave a lasting impress on the son who came to her in her twenty-seventh year.

In 1841 Carolus Laurier proudly recorded the following entry in his papers:

(Translation)

To-day, the twenty-second day of the month of November, in the year of Our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and forty-one, was baptised in the church of St. Lin, by Messire G. Chabot, curé for the said parish, Henri Charles Wilfrid, born the twentieth day of the present month, of the lawful marriage of Carolus Laurier, gentleman, land-surveyor, and Marie Marcelle Martinault. His godfather is Sieur Louis Charles Beaumont, Esq., gentleman, of Lechenaie; his godmother is Marie Zoé Laurier, wife of Sieur L. C. Beaumont.

On January 23, 1844, he records the birth and baptism that day of Marie Honorine Malvina Laurier.

Marcelle Martineau was not fated to be with her children long. She died in March, 1848, in her thirty-fifth year. But in the seven years of her son's life with her, she had so knit herself into his being that the proud and tender memory of her never faded from his deeply impressionable mind. A second blow came with the death,[27] when barely eleven, of the sister who had grown very dear to him.

Carolus Laurier soon took a second wife, Adeline Ethier. By this marriage there were five children: Ubalde, who became a physician and died at Arthabaska in 1898; Charlemagne, for many years a merchant at St. Lin, and member for the county of L'Assomption in the House of Commons from 1900 until his death in 1907; Henri, prothonotary at Arthabaska, who died in 1906, and Carolus and Doctorée (Mme. Lamarche), both of whom survived their half-brother.

Adeline Laurier proved a very kindly and capable mother to all her flock. Her hold on the elder boy's warm affections, and incidentally her husband's light-hearted outlook on life, are brought out in a letter which Carolus wrote to a niece of his wife, many years after:

(Translation)

St. Lin, March 19, 1886.

I am almost certain to get well in spite of my seventy-one years, and I embarked on the seventy-second the day before yesterday, while the Irish were holding their procession in the streets of Montreal, and as that day is the day of their patron saint and their national festival, and as I came into the world 71 years ago, I think that is the reason why, when I was a widower, 5 or 6 old Irish damsels from New Glasgow used to come to mass at St. Lin every Sunday and my seat was always full of them. But the moment I married your aunt, pst! their devotion was at an end, and I found myself rid of these old girls, and my seat and the rest of the church likewise.

... That did not prevent me keeping my health and being very happy with your aunt, and my children too, for I am certain that Wilfrid loves his stepmother just as if she was his own mother. I always remember that at the age of eleven,[28] when he came home from school, he would go and sit on his stepmother's lap to eat his bread and jam or bread and sugar, with his arms round her neck, and that he would put his "piece" on his knees and wipe his mouth with his handkerchief and kiss her over and over, and then pick up his "piece," eat a few mouthfuls and begin to kiss her again....

Carolus L.

St. Lin in the early fifties was a prosperous frontier village. Twenty miles to the north the blue Laurentians set a barrier to further expansion. The village itself was the centre of a broad, fertile, slightly rolling plain, still covered for the most part with the maples and elms, the pine and spruce, of the primitive forest. Its great stone church towered high above the houses that lined the two straggling streets. The river Achigan, on which it lay, turned the wheels of the grist-mills on its banks, floated down the logs from the upper reaches, and, not least, provided fishing and swimming-holes for boys' delight. It was a quiet, pleasant home, well devised to give its children happiness in youth, strength in manhood, and serene memories in old age. Young Laurier shared in the usual children's games, though an old companion recalls that many a time when the boys would call, "Wilfrid, come, we are ready for a race," the answer from the boy bent over a book would be, "Just a minute," and again, "A minute more." He particularly delighted in wandering through the woods, sometimes with gun on his shoulder for rabbit or partridge, but more often with no other purpose than to search out bird and plant and tree. His sharp eyes and retentive memory gave him an intimate and abiding [29]knowledge of wood life of which few but his closest friends in later days were aware.

The boy's early schooling was given partly by his mother and partly in the parish school of St. Lin. Under the French régime a fair measure of elementary schooling had been provided, mainly by the religious orders, but with diversion of endowments to other ends and disputes between Church and State as to control, progress after 1763 had been slow. It was not until 1841 that an adequate system came into force. In the school in St. Lin, which is still standing, though no longer used as a school, the children of the late forties learned their catechism and the three R's. For the majority, no further training was possible. For the few who were destined for the Church, the bar or medicine, the classical college followed. In young Laurier's case a novel departure was taken.

Some seven miles west of St. Lin, on the Achigan, lay the village of New Glasgow. It had been settled about 1820, chiefly by Scottish Presbyterians belonging to various British regiments. Carolus Laurier in his work as a surveyor had made many friends in New Glasgow, and had come to realize the value of knowledge not only of English speech but of the way of life and thought of his English-speaking countrymen. He accordingly determined to send Wilfrid, at the age of eleven, to the school in New Glasgow for two years. Arrangements were made to have him stay with the Kirks, an Irish Catholic family, but when the time came illness in the Kirk household prevented, and it was necessary to seek[30] a lodging elsewhere. One of Carolus's most intimate friends was John Murray, clerk of the court and owner of the leading village store. Mrs. Murray took in the boy and for some months he was one of the family. The Murrays, Presbyterians of the old stock, held family worship every night. Wilfrid was told that if he desired he would be excused from attending, but he expressed the wish to take part, and night after night learned never-forgotten lessons of how men and women of another faith sought God. When Mrs. Kirk recovered, he went to her for the remainder of his two years in New Glasgow, but he was still in and out of the Murrays' every day, and many a time helped behind the counter in the store. The place he found in the life of the Kirks may be gathered from a passing remark in a letter from his father forty years later: "Nancy Kirk writes that her father is now over a hundred and beginning to wander in his mind: 'he does not see us at all, but talks of Wilfrid and of Ireland.'"

The school in New Glasgow was open to all creeds and was attended by both boys and girls. It was taught by a succession of unconventional schoolmasters, for the most part old soldiers. The work of the first year in New Glasgow, 1852-53, came to an abrupt end with the sudden departure of the master in April. A man of much greater parts, Sandy Maclean, took his place the following year. He had read widely, and was never so happy as when he was quoting English poetry by the hour. With a stiff glass of Scotch within easy reach on his desk, and the tawse still more prominent, he drew on[31] the alert and spurred on the laggards. His young pupil from St. Lin often recalled in after years with warm good-will the name of the man who first opened to him a vision of the great treasures of English letters.

The two years spent in New Glasgow were of priceless worth in the turn they gave to young Laurier's interests. It was much that he learned the English tongue, in home and school and playground. It was more that he came unconsciously to know and appreciate the way of looking at life of his English-speaking countrymen, and particularly to understand that many roads lead to heaven. It was an admirable preparation for the work which in later years was to be nearest to his heart, the endeavour to make the two races in Canada understand each other and work harmoniously together for their common country. Carolus Laurier set an example which French-speaking and English-speaking Canadians alike might still follow with profit to their children and their country.

New Glasgow was only an interlude. Carolus Laurier had determined to give his son as good a training as his means would allow. That meant first a long course in a secondary school, followed by professional study for law, medicine or the Church, the three fields then open to an ambitious youth. Secondary education in Lower Canada was relatively much more advanced than primary; the need of adequate training for the leaders of the community had been recognized earlier than the need or possibility of adequate training for all. The petit séminaire at Quebec and the Sulpicians' col[32]lege at Montreal had trained the men who led their people in the constitutional struggles following 1791. Secondary schools or colleges, modelled largely on the French colleges and lycées, had early been established in the more accessible centres, in 1804 at Nicolet, in 1812 at St. Hyacinthe, in 1824 at Ste. Thérèse, in 1827 at Ste. Anne de la Pocatière, and in 1832 at L'Assomption. All were maintained and controlled by the Church.

In September, 1854, Wilfrid Laurier entered the college at L'Assomption in the town of the same name, on L'Assomption River twenty miles east of St. Lin. Here for seven years he followed the regular course, covering what in English-speaking Canada would be taken up in high school and the first years of college. The chief emphasis was laid on Latin; the good fathers succeeded not merely in grinding into their pupils a thorough knowledge of moods and tenses, but in giving them an appreciation of the masterpieces of Roman literature. Many a time in later years when leaving for a brief holiday Mr. Laurier would slip into his bag a volume of Horace or Catullus or an oration of Cicero, and, what is less usual, would read it. French literature was given the next place in their studies, the literature, needless to say, of the grand age, of Bossuet and Racine and Corneille, not the writings of the men of revolutionary and post-revolutionary days, from Voltaire to Hugo and Béranger. Briefer courses in Greek, English, mathematics, philosophy, geography and history completed the seven years' studies. It was a training of obvious limitations, but in the hands of good teachers such [33]as the fathers at L'Assomption were, it gave men destined for the learned professions an excellent mental discipline, a mastery of speech and style, and a sympathetic understanding of the life and culture of men of other lands and times.

The school discipline at L'Assomption was strict. The boys rose at 5:30, and every hour had its task or was set aside for meal-time or play-time. The college had not then built a refectory, and the students, though rooming in the college buildings, scattered through the town for their meals. Every Sunday, garbed in blue and black coat, collegian's cap, and blue sash, all attended the parish church; on week-days only the sash was worn. Once a week, on Thursday afternoons, there came a welcome half-holiday excursion to the country, usually to a woods belonging to the college a few miles away. [5] These excursions young Laurier enjoyed to the full, but he was not able to take much part in the more strenuous games of his comrades. The weak[34]ness which was to beset his early manhood was already developing, and violent exercise had been forbidden. His recreation took other forms. The literary part of the course, the glories of Roman and French and English literature, made a deep appeal to him. He took his full share in the warm and dogmatic discussions in which groups of the keener youngsters settled the problems of life and politics raised by their reading or echoed from the world outside. Sometimes a nearer glimpse was given of the activities of that outer world. Assize courts were held twice a year, and when election-time came round, joint debates between the rival candidates at the church door after Sunday mass or from improvised street platforms on a week-day evening were unalloyed delight. More than once he broke bounds to drink in the fiery eloquence of advocate or politician, well content to purchase a stimulating hour with the punishment that followed.

Wilfrid Laurier had come to L'Assomption with a strong leaning toward Liberalism. His father's freely spoken views, discussions of his elders overheard in St. Lin and New Glasgow, echoes of the eloquence of the great tribune Papineau, the reading of the history of Canada which Garneau had written to belie Durham's charge that French-speaking Canada had no literature, had awakened political interest and given him the bent[35] which his own temperament and his later reading confirmed. If the seed had not been vital and deeply planted, his Liberalism could scarcely have survived the Conservative atmosphere of L'Assomption. When the French-Canadian majority which had fought solidly for self-government divided, once self-government was attained, into Liberals and Conservatives, the great mass of the clergy, as will be noted later, took the Conservative turning. The college authorities and the great majority of his fellow-students looked with more than suspicion on his political heresies. When a debating society which young Laurier had helped to organize ventured on still more dangerous ground, taking up the highly contentious theme over which historians have shed quarts of ink: "Resolved, that in the interests of Canada the French kings should have permitted the Huguenots to settle here," and when the student from St. Lin took the affirmative and pressed his points home, the scandalized préfet d'études intervened, and there was no more debating at L'Assomption. Yet these differences were not serious. The relations between teachers and pupils were very friendly. Young Laurier was soon recognized as the most promising student of his time, and it was with pride that the authorities and his fellows chose him to make the orations or read the addresses on state occasions.

Students of all political tendencies and of none were graduated from L'Assomption. It was the alma mater, though in the days before the rise of parties (1835-42),[36] of the giant Rouge tribune, Joseph Papin, le gros canon du parti démocratique, who is still commemorated in the college halls, with laudable impartiality, as vir statura, voce et dialectica potens, and of Léon Simeon Morin (1841-48), his brilliant Conservative opponent, who shot like a fiery meteor across the political sky of Canada. Louis A. Jetté, founder of the Parti National which sought to reconcile Liberalism and the Church, and later an eminent judge, left L'Assomption the year before Wilfrid Laurier entered. Arthur Dansereau, for many years the leading Conservative journalist in Quebec, was a year his junior, while in his last year there entered a young lad from Lanoraie whose path was to cross his many a time in the future, the stormy petrel of Quebec politics, J. Israel Tarte.

The seven years soon passed and the momentous day of graduation came. Of the twenty-three members of his class (the 22nd "course") only nine completed the seven years. The interests of the class were well divided. Of the later career of three, two of whom went to the Western States, no record is available. Of the other twenty, three became barristers (avocats) and three notaries, these six providing the three who won legislative honours; four became priests, four doctors, and three farmers, two entered business, and one died while at school.

Wilfrid Laurier's ambitions had long been turned toward law, and when he left L'Assomption at the age of nineteen it was with the purpose of beginning immediately to study for the bar. The leading law school of [37] Canada was then the Faculty of Law at McGill University. It had a strong staff of judges and of barristers in active practice, and the offices of the city gave ample opportunity for training in the routine of law. The law faculty of Laval University, Montreal, it may be noted, was not established until 1878.

To Montreal, then, Wilfrid Laurier journeyed in the fall of 1861, with high hopes but some foreboding as to what life in a large city would mean. He found a place in the office of Rodolphe Laflamme, one of the leaders of the Montreal bar and a very aggressive Rouge or advanced Liberal. The salary paid, though small, was a very welcome supplement to the funds his father had been able to advance.

The three-year course, which led to the degree of Bachelor of Civil Law, covered not only the basic systems of our jurisprudence, the civil law of Rome and the common law of England, but the developments which custom and legislators and code-makers had brought about in English-speaking and French-speaking Canada. The lectures were given in English or French, according to the mother tongue of the speaker. Mr. Laurier, with his New Glasgow training and his later reading, had no great difficulty in following the English lectures. He had more trouble at first in understanding the Latin phrases in the lectures on Roman law delivered by Justice Torrance, for at that time the English pronunciation of Latin was almost the universal rule among English-speaking scholars. Hon. J. J. C. Abbott, dean of the faculty, and destined thirty[38] years later to become in a party emergency Prime Minister of Canada, was a sound and authoritative teacher of commercial law. Rodolphe Laflamme taught customary law and the law of real estate, and Hon. Wm. Badgeley and E. C. Carter criminal law. Throughout, Wilfrid Laurier ranked high in his work, though for the comfort of those students who gather instances of men succeeding in examinations and failing in the sterner tests of life, it may be noted that the one man who ranked higher was never heard of again. In his first and again in his third year, he stood second in general proficiency, and at graduation was first in the thesis required of all candidates for the degree. He was accordingly chosen to give the valedictory. It is not customary to find in student valedictories mature and original contributions to the philosophy of life. The address given on this occasion had its share of the rhetoric of youth, but it was a really notable utterance. The young valedictorian sketched a picture, somewhat idealized perhaps, of the lawyer's place in the nation's life, forecasting in more than one particular the principles which were to guide his own public career. The duty and the opportunity of the lawyer to maintain private right, to uphold constitutional liberty, and to work for the harmony of the two races in Canada, were strongly emphasized in vigorous and glowing phrase.

Valedictories butter no parsnips. No time could be lost in seeking to make a living. Mr. Laurier was admitted to the bar of Quebec in 1864, and in October of that year began practice in Montreal as a member of the firm of Laurier, Archambault and Désaulniers.[39] All three partners were keen and ambitious, but the city seemed well satisfied with the old established firms, and clients were few. Finding difficulty in tiding over the months of waiting, the partners dissolved in April, 1865. Mr. Laurier then formed a partnership with Médéric Lanctot. Lanctot was a fiery and brilliant speaker, of unbounded energy and audacity, but poorly ballasted with judgment and fated for all his lavish endowment to wreck his career. The partners were curiously assorted—the older man eager, passionate, fond of lively company, ready to debate any question in heaven above or earth beneath; the younger, reserved, retiring, firmly rooted in his convictions but calm and balanced in their defence. Lanctot was absorbed in politics, writing, speaking, organizing petitions against Cartier's Confederation policy. Laurier was left to carry on most of the work of the office. Their rooms were the meeting place of an eager group of young lawyers, burning with opinion or phrases on the political issues of the day, and in Quebec fashion turning lightly from law to journalism. Ill-health and his reserve and moderation of temper kept Mr. Laurier from taking an active part in their discussions, but friendships were formed and opinions shaped which counted for much in after years.

The question of his health was in fact now giving him serious concern. Throat and lung trouble had developed, accompanied by serious hemorrhages. Many of his friends felt that a quiet country town would give a better fighting chance than a crowded city. Antoine Dorion, his most valued friend, and the Liberal leader[40] in Canada East, [6] advised him to open a law office in the growing village of L'Avenir, in the Eastern Townships, and to combine with the law the editing of the weekly newspaper, "Le Défricheur," which Dorion's younger brother, Eric, had founded and managed until his death in 1866. Mr. Laurier felt that the advice was sound, and in November, 1866, he left Montreal for the little backwoods village. A brief residence convinced him that in spite of its optimistic name L'Avenir had no future, and accordingly he moved his newspaper and his law office to Victoriaville, thirty miles further east. While Victoriaville, as the railway centre of the district, became in time the chief business town, Mr. Laurier concluded that his law practice would flourish more securely in the judicial centre or, chef lieu of the district, St. Christophe, or, as it was later termed, Arthabaskaville, and early in 1867 he opened his office in the picturesque little town which was to be his home for the next thirty years. [7]

One further personal episode, and that the most important of his career, remains to be chronicled before sur[41]veying the beginnings of his public interests and activities in Montreal and the Townships.

When Wilfrid Laurier first came to Montreal he knew little of the city or its people—his only memory of it a child's awe-struck vision of endless houses and endless people, glimpsed from a crowded seat in a carriole, a dozen winters before. Neighbours in St. Lin reminded him of a close friend of his mother, Mme. Gauthier, whose husband had been the village doctor in Marcelle Laurier's short married life. Dr. Gauthier was now practising in Montreal. The young student went to their home, and lived with them two of his five Montreal years.

Both Dr. and Mme. Gauthier were much interested in music and both were hospitably inclined. They kept open house for a wide circle of young people of like tastes. In this group Wilfrid Laurier took his place, but it was within the house that he found his absorbing interest. Mme. Lafontaine and her daughter Zoë were also living at the Gauthiers'. Not many months had passed before the vivacious charm, the piquant blending of deep kindliness and straight-spoken frankness, the wit and judgment, and the musical gifts of Mlle. Lafontaine had completely captured young Laurier's heart. Nor was it long until Mlle. Lafontaine had come to feel that this quiet young man of reserved but assured power, of strikingly handsome figure, of unfailing courtesy to all about him, who had already an air of distinction and a touch of the grand seigneur which[42] made all eyes follow him, was the centre of her world. But he was as yet only a student at law, and she was earning her living as a teacher of music. Marriage seemed out of the question for long years. Then came the increasing grip of illness on his frail body, and the removal to Arthabaskaville without any definite understanding between them. [8]

[43]Separation and time did not weaken affection, but neither did they remove the barriers. There were weeks of doubt when Mr. Laurier was convinced that his days were numbered and that he could not fairly ask any girl to share them. Then would come days of hope and determination, and in his letters he would insist that he could and would recover. In the meantime other suitors were pressing, and particularly a physician in good practice and good circumstances in Montreal. Prudence, friends urged that it was quixotic to refuse this suitor because of an interest in a struggling country lawyer, with a most uncertain lease of life. The pressure won. The engagement of Mlle. Lafontaine and her Montreal suitor was announced. Then ten days before the marriage was to have taken place, Fate, in the cheery person of Dr. Gauthier, intervened. He telegraphed Mr. Laurier to come to Montreal at once on important business. He came, saw, conquered. The young couple determined to heed their own hearts and their own half-believed hopes. In reality Mlle. Lafontaine did not believe that their married life would be longer than a year or two, but if she could make her husband's life happier and easier for that time, she was prepared to make the venture. Action followed quickly. A special dispensation was secured, and at [44]eight o'clock that evening, May 13, 1868, Wilfrid Laurier and Zoë Lafontaine were married. As he had to appear in court in Arthabaskaville next morning, he left at ten the same evening, returning three days later to take Mme. Laurier back to their new home. They had challenged fortune, and fortune yielded to their faith. Soon the shadows lifted, and they entered on fifty years of rare happiness and close communion. That was for the future to disclose, but already in marrying Mlle. Lafontaine, Wilfrid Laurier had achieved half his career.

The Union Era—The Reshaping of Parties: Responsible Government—Bédard and Papineau—Papineau and LaFontaine—The Rise of the Rouges—The Liberal-Conservatives—Parties at Confederation—The Rise of Nationalism: A Conflict of Races—Laurier on Durham—The Failure of Durham's Policy—Barriers to National Unity—Laurier and Confederation—Church and State: The Church under Two Regimes—The Rouges and Rome—The Passing of L'Avenir—The Institute Controversy—Laurier and Le Défricheur.

IN the Canada of the sixties a young man's fancies lightly turned to thoughts of politics. Public life dominated the interest of the general public and stirred the ambition of the abler individuals in far greater measure than is true in these days when business makes a rival appeal. Particularly in Lower Canada, a political career was the normal objective, or at least the visioned hope, of the majority of the young men of education and capacity.

From boyhood days Wilfrid Laurier had been keenly interested in public affairs. His student apprenticeship and his first years of practice in Montreal gave an opportunity for forming political connections and taking a part in public controversies which strongly confirmed his early leanings. Now, as editor of the chief democratic journal of the Eastern Townships, he was a chartered guide of public opinion. His law practice brought him into close contact with all parts of the district, and before five years had passed he was marked as the des[46]tined standard-bearer of the Liberals of the county.

Wilfrid Laurier was born in the year that Upper and Lower Canada were yoked together in uneasy fellowship. He had just begun the practice of law at Arthabaskaville when the union of the two Canadas was dissolved and the wider federation of all the mainland provinces was achieved. It was in the Canada of the Union era that the stage was set and the players trained for the comedies and the tragedies, the melodrama and the vaudeville, of Confederation politics.

The stage was not a large one. The province of Canada was just emerging from its years of pioneer struggles and backwoods isolation. Its two million people seemed to count for little in the work of the world. Neither Britain nor France nor the United States gave them more than a passing thought. Even with the other provinces of British North America they had little contact: no road or railway bound them. Until well on in the Union period, each section had closer relations with the adjoining states than with its sister provinces—Upper Canada with "York" State, Lower Canada with New Hampshire and Vermont, and the Maritime provinces with Maine and Massachusetts.

Yet if it was not large, the provincial stage witnessed its full share of the dramatic motives and movements of political life. Here experiments were worked out in the organization of government and of parties, in the relation of race with race, in the connection between Church and State, and in the linking of colony and empire, which deeply influenced the development of the[47] future Dominion and were not without interest to the world beyond.

In the words of Mr. Laurier, in an unpublished fragment of a work he long planned to write, had fate given him leisure,—the political history of Canada under the Union,—

A new era began with the Union. In this new era there was found nothing of that which had given the past its attraction, neither the great feats of arms to save the native soil from invasion, nor the intrepid journeys of the explorers led on and on by an unquenchable thirst for the unknown, nor the journeys, more intrepid still, of the missionaries everywhere marking with their blood the path for the explorers. The very parliamentary battles on which henceforth the attention of the nation was to be concentrated no longer bore the striking impress which had been stamped on the parliamentary struggles after the Conquest by the prestige of those who took part in them, the greatness of the cause which was defended, and the bloody catastrophe which was their outcome.

Colourless these pages may be, but they are not barren. They recall an epoch which, in spite of failures, was on the whole fruitful, in which the patriot's eye may follow with legitimate pride the calm, powerful and salutary influence of free institutions. [9]

The tasks of government and the scope and organization of parties had been greatly modified by the union of Upper and Lower Canada in 1841. The Union Act brought together two communities of deeply varying ways and traditions, communities which for fifty years had had their separate governments and their local parties. The mere union of the two provinces would have made it necessary to shift the bases of political activity, but union further brought in its train respon[48]sible government, and responsible government involved as an essential condition the existence of political parties more definite and coherent than had hitherto existed in the Canadas.

The insistence of the Reformers of Upper Canada and the Patriotes of Lower Canada, through years of struggle, upon a greater share in their own governing, and the shock of the rebellion of 1837, had compelled British statesmen to recognize at last that concessions must be made. Under Durham's guidance, they had come to see that the concession should take the form which Robert Baldwin, the leader of the Upper Canada Reformers, had long demanded—the grant, in some measure, of responsible government. Responsible government meant in essence that the administration of the country should be entrusted to the leaders of the dominant party in parliament, rather than, as in the past, to the governor and the bureaucrats whom he appointed. But how could such freedom, even with the restrictions with which in early years the concession was hedged about, be granted to a colony like Lower Canada, where the majority would inevitably be composed of French-Canadians? English statesmen could bring themselves, with difficulty, to admit the need of self-government for the colonists of English speech and traditions in Upper Canada, but to propose the same policy for a colony alien in blood and tongue and sympathy appeared to them beyond discussion. Only by uniting the provinces, to assure an English-speaking majority, could the experiment be risked. Nor was the Union [49]only negatively directed against French-Canadian aspirations. Its framers hoped to make Union a positive means of anglicizing French Canada, of bringing the habitant to realize the folly of isolation in a continent of English speech. How they fared in this endeavor will be noted later.

The primary task of the forties was the winning and consolidation of responsible government. Governor after governor and tenant after tenant of Downing Street sought to set narrow bounds to the concession that had been found unavoidable, but in vain. Robert Baldwin, "the man of one idea," and Louis Hippolyte LaFontaine, leader, in Papineau's enforced absence, of the Lower Canada Liberals, stood firm in their insistence that complete control of the domestic affairs of the province must be conceded to a body of ministers responsible to parliament and chosen from its dominant parties. Sydenham fought their demands, but by making himself the leader of a party majority in the Assembly played into the hands of those who insisted that party majorities should rule. Bagot, less assertive in temper, made some concessions of intention and more through the accident of illness. Metcalfe, sent out by the Colonial Office as the last bulwark of authority, breasted the tide with success for a year or two, but at last was compelled to recognize his failure. Elgin, the last of the governors of the forties, gave formal recognition of the victory of the upholders of self-government by summoning LaFontaine and Baldwin to form the ministry of 1848.[50]

On this question of responsible government, the conclusions of Mr. Laurier, embodied in the same pregnant fragment, are of particular interest because of his early relations with the Rouges and the exponents of the Papineau tradition, and his own long experience of the working of the system:

Thus Lord Durham's idea had been realized, but its realization had only been gradual. The theory of Lord John Russell continued to be the theory of Lord Sydenham, of Sir Charles Metcalfe and of the Colonial Office, until Lord Elgin, who to the generous spirit of Lord Durham added a capacity perhaps more solid, grasped the great reformer's idea and applied it with as much freedom as he himself would have done.

If, to the England of 1840, the idea of the responsibility of ministers appeared incompatible with the colonial status, the colony was more advanced on this point than the mother country.

In Upper Canada a large group, more important even for talent than for numbers, had long been demanding the responsibility of ministers to the Assembly. The men of this party had found in Lord Durham's report the expression of the ideas which they had long been professing. They had voted without hesitation for the proposal for union, because they had hoped that Lord Durham's report would be acted upon in its entirety. Nevertheless, it was not in Upper Canada, nor in the British population [of Lower Canada] that the idea of ministerial responsibility as applied to the government of the colonies had seen the light for the first time. The man who was the first to affirm the principle of ministerial responsibility in the government of the colonies was Joseph Bédard, and that as early as 1809. Nevertheless, this weighty suggestion had not been followed up. A few years later, Bédard had withdrawn from the arena and Mr. Papineau had entered it. The policy enunciated by Bédard had been set aside, to give place to another much bolder. In all the long struggles that Mr. Papi[51]neau carried on with the government, he does not seem ever to have dreamed that the concession of constitutional government might be a sufficient reform and that he himself might become the minister in control. All his efforts were unceasingly directed toward establishing the supremacy of the Assembly over the executive power, and toward making the executive power the executor of the will of the Assembly. Under a constitutional monarchy, it is true, the ministry exists only with the consent of the elective branch, but in reality, it is the ministry that dominates the Assembly. The Assembly has numbers and strength, but it allows itself to be led and dominated until the time when, changing its mind, it resumes its power only to let itself be dominated once more by others. This system is doubtless not the perfect ideal that a thinker might dream of, nevertheless it is the system, of all invented by man, which has taken away least of individual liberty. This is not the system that Mr. Papineau sought. Mr. Papineau seemed to conceive a state of things in which in point of fact the Assembly would be sovereign, and in which the Administration's sole duty would be to carry out its decrees. Everything was subordinated to secure this result, and certainly, if it had been secured, it would have been good enough. Yet Mr. Papineau's thought went much farther still. In the debates on the 92 resolutions, he allows us to see clearly his republican ideals: "It is the obvious destiny of the continent, and since a change must be made in our constitution, is it a crime to make it with this conjecture in view?" The man who used such words could have only one end in view: independence.

Responsible government meant party government. Only through party organization could there be assured a stable and united majority to back the ministry in power, and a definite opposition to criticize that ministry and stand prepared to provide an alternative administration. And yet the very winning of responsible[52] government, and the union of the provinces which was bound up with it, made it extremely difficult to find or keep stable and effective political parties.

The weakness and instability of parties in this period had two roots. One was the union of the provinces, a union which brought together extremely diverse elements and yet was not sufficiently complete to merge and fuse them. Union made it necessary to organize a majority not in one section alone but in the whole province, and to organize it out of parties which hitherto had had little contact or little in common. At the same time the incomplete and semi-federal character of the union prevented the complete assimilation which the smooth working of the party machinery demanded. From the beginning there had been a recognition of continuing separateness in the provision that each section of the province, irrespective of population, should be given half the number of representatives in the legislature. As time went on, this separateness was confirmed by the practice of passing laws applying only to one section, by holding the sessions of parliament alternately in Quebec and in Toronto, by the inclusion in the cabinet of both an Attorney-General West and an Attorney-General East, and by the custom of a double-barrelled leadership, two "premiers," LaFontaine-Baldwin, Macdonald-Cartier, Brown-Dorion. It was inevitable under such circumstances that any union of parties from Canada East and Canada West should be, not a complete merging, but only a coalition of more or less stability.[53]